I never knew my Aunt Dess. She died when I was only three years old, so I don’t have any memories of her. Other siblings and cousins have said that she could be mean, and was a bit…unusual. You see, by all accounts Odessa Lee Taylor Poole, younger sister of my grandfather, was one of the last of the granny witches.

In the strict Pentecostal Holiness environment in which I was raised, any thought of witchcraft was strictly forbidden. I’m sure if you asked any of the older generation they would strongly deny this label, and would laud Aunt Dess as a church member and fine Christian woman. Most of my evidence about her comes from my sister and my cousins – evidence faded with the years and the perspective of adulthood. But, the tales are still intriguing.

My Great-Grandfather Robert Taylor lived in a small white house on Yarborough Mill Road near Wattsville. That house is still standing. I visited it many times when my Uncle Charlie lived in the house and one of his daughters still lives there with her family. It was in this house that Odessa Lee was born and raised with her eight siblings, including my grandfather. The story goes that on the back side of the property lived a Cherokee woman who taught Odessa her craftwork. My cousin Ron described Odessa this way on her Find-a-Grave listing:

Odessa Lee Taylor was the 4th child of Robert Whitner and Sarah Elizabeth Todd Taylor. She married Boyce B. Poole (son of Gus and Mary Duvall Poole of Clinton, SC). They had no children. She lived near her parents for most her he life. From an old Cherokee woman who lived next door, she learned how to conjure. Family story relates that when the flu was raging and her brother’s family all had it, Odessa went to his barn, cut the cow’s tuft from its tail, drew a circle in the back yard and burned it in the circle to prevent death in his family. Most of her brothers and sisters believed in the signs.

According to my sister, Glynda, Odessa was “more into cursing than healing.” The couple was childless, and Aunt Dess had an antipathy toward children. Glynda remembers her as always being “mean,” fussing at the cousins that crossed her or did something she thought was out of line. If she saw children playing in the yard turning cartwheels, or just being kids, her favorite line was, “You’re gonna turn your liver over and die!” (I’ve actually heard my own grandmother repeat that line in all seriousness. Apparently this was a common southern superstition, although others spoke of turning one’s liver over by laughing, as if it were a good thing, like turning over a new leaf. I guess it depended on your point of view.)

Uncle Boyce was the complete opposite of Aunt Dess. He was tall and gangly, and friendly with the cousins. It was said that he was pious to a fault, so much so that he would collect the lint that gathered in his pockets while working at Watts Mill. He would then return it to the mill the following day, as it did not belong to him. How such a man could put up with the likes of Aunt Dess is either a testament of their love, or a testament of her power over him.

When Boyce and Dess married they moved into a new home on Patton Avenue, less than a quarter of a mile from and within view of Dess’s parents’ home. Glynda said that weird jars with even weirder contents hung from the railing on their back porch. The cousins swore that these were used in Odessa’s conjuring. There was a shed out back that was forbidden to the children. Of course, any place off limits is open to speculation, especially given the character of my great-aunt.

When Uncle Boyce passed away Aunt Dess descended into a state of chaos, wailing and moaning. No one thought she should be left alone. Cousins Ronnie and Bob Taylor, along with my brother Houston, were tasked with keeping her company the night after the funeral. They were all of ten and twelve years old, and very susceptible to strange signs and visions, as kids that age often are. Boyce and Dess’s house was surrounded by other cousins’ houses, and was just two doors down from my grandparents, so it wasn’t as if they were totally alone. However, strange things did happen. They reported that Aunt Dess wandered throughout the house that night clapping two silver spoons together, along with mutterings, incantations, and injunctions to ward off the spirit of the departed Uncle Boyce. Bob claims that he saw the ghost of Uncle Boyce wandering the house, just out of reach of Aunt Dess.

Years later my dad’s brother, Uncle Joe, and his wife Jesse moved into Boyce and Dess’s old house with their three sons, David, Ronnie, and Bob. I’ve spent many a night in the house myself, but never witnessed anything out of the ordinary. As an adult, Bob lived in the house on Patton Avenue. There was a gas heater for the bathroom, and he had fallen asleep with the gas still on. He was shaken roughly out of his sleep by some force, and realized that he was in danger from gas poisoning or from explosion. To this day Bob thinks that Aunt Dess was unsuccessful in removing Uncle Boyce, and that his spirit still inhabits the house, looking after his nieces and nephews.

World folklore is replete with tales of granny witches, whether they are called babushkas, ya-yas, or some other appellation. The archetype of a wizened old folk healer appears in both male and female forms. These tales often show up in places where doctors are rare, and folks have to make do with whatever is at hand. To simple folk their abilities may have seemed magical, hence the prevalence of “fairy godmothers” in so many stories.

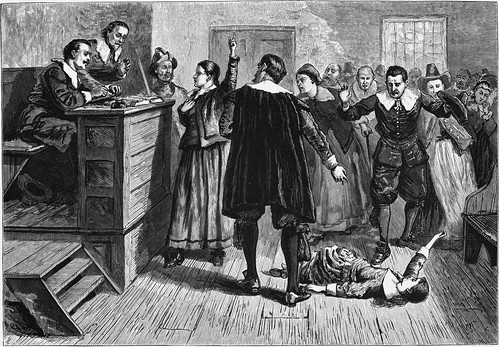

Then there’s the darker side – tales of supposed black magic and witch hunts. If Aunt Dessa had been born a couple hundred years earlier, she might not have been received as kindly. In 1792 in Fairfield County Mary Ingelman suffered a much worse fate, in the most notorious witch trial in South Carolina.

Mary Free Ingelman was a classic granny witch. She was from Germany, and had been trained as a folk healer. Sadly, any hidden knowledge, such as the knowledge of healing herbs, leads to thoughts of witchcraft. From the accounts I’ve read, she got into a dispute with her son from her first marriage, Adam Free, over the ownership of a cow. Adam and his son, Jacob, accused Mary and three other members of the community of being witches.

An illegal trial was held by the local sheriff in Winnsboro. The four were horribly tortured by fire, but were allowed to live. Unlike the unfortunate victims of the Salem Witch Trials, Mary Ingelman was able to get some measure of justice. She sought legal redress against the sheriff and prosecutor, a Mr. Crosland. The courts found for Mary, and Crosland was fined fifty pounds sterling, or about $125 in today’s coin.

Tales of folk healers, root doctors, and even witch doctors still persist in the Appalachians and along the southern coastal states. The image of “Minerva” from “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil” comes to mind. Minerva was a fictional character based on John Berendt’s book. Berendt’s book, in turn, was supposed to be based on actual events, and describes the book’s narrator’s interactions with a root doctor in Beaufort County, the late Valerie Fennel Aiken Boles.

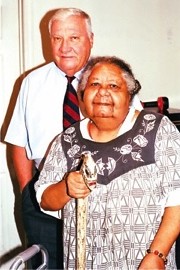

Berendt’s root doctor character aside, there are other tales of healer women in the Carolinas. One of the most famous and respected healers was Phoebia Cheek Sullivan.

Madame Sullivan grew up near my home of Gray Court. She was born in the Dials Church Community, near my great-grandparents’ home place. The date of her birth is questionable. One source says that she was “born to former slaves on May 15, 1864” and others give her date of birth as 1855.

At an early age Phoebia was told that she had “healing hands” by a Doctor Wolfe, local doctor for the Dials Township. One source says that Dr. Wolfe had at one time owned Phoebia’s father as a slave. She married Henry Sullivan and reportedly had sixteen children – some mixture of her own and adopted.

The family lived in Dials in abject poverty. The children were malnourished, and Phoebia herself became deathly ill. During her illness she had a dream. The Asheville Citizen-Times described the events in a 1960 article.

That night she had a strange dream – the first in a series of dreams which she was later to publish in a “Book of Dreams.” The Lord had come to see her while she slept, and told her what to do…

“Wrap me in white sheets and carry me out into the woods,” she said excited to those who had come to help her. “Bring me something to dig with,” she added

Lord have mercy! Was Phoebia going out in to the woods to die? Would they have to dig her grave?

“The Lord told me where to find the roots and herbs that’ll make me well,” said Phoebia as her friends wrapped her in sheets.

While she was carried through the woods Phoebia looked at her black hands against the white sheet wrapped around her body. She could see the story of coming events: black hands surrounded by white: black hands serving, healing.

Reports were that Phoebia had a miraculous recovery after drinking her concoction. Word spread, as did her reputation as healer.

The large Sullivan family moved to Greer, SC. After the death of Henry Sullivan, Phoebia moved her large family to the mountain town of Saluda, NC in about 1926. That is where her reputation as a healer took off. As she had seen in her dream, she served both the black and white communities in the Saluda area. According to the Historic Saluda website…

Slowly the word passed through the then sizable black community of her elixir and her healing abilities and the world began to literally beat a path to her door. There are still many in Saluda who remember the pilgrimage of countless blacks and many whites who made the stop on the train at Saluda for a jug of the brew. Of those who came few were disappointed.

Some came to drink her cleansing tea and others more seriously ill felt her touch. Her daughter Lula Sullivan who came to live with her in the early 1950s, remembers the numbers of the desperately sick who passed through her doors.

“I’ve seen them come in on stretchers,” she attests, “and walk out by themselves. Wherever she was in the house, they would lay them before her. And Mother would lay her hand upon Her proudest accomplishment, however, was the founding of the Sullivan Temple Missionary Baptist Church in 1947, a church in which her son James became an assistant pastor. But Madame Sullivan never preached in her church, for she didn’t give sermons as such. Instead, she quoted the Bible at length and those who knew her remember her scope in recitation as extraordinary. She could quote from the Bible verbatim for hours, although it’s unclear how she came by her knowledge since she couldn’t read and others had to handle her correspondence and read to her.

During the waning years of her life she remained robust and was a familiar sight walking down Greenville Street into town. “She looked like an angel with her snow white hair and the white apron she always wore.” remembered Lola Ward. “She was a beautiful woman.”

A 2015 article in Blue Ridge Now further describes Phoebia Sullivan’s work in the community:

The Rev. Maxine Wilkerson of Saluda remembers health seekers queuing up to Sullivan’s door. “They’d stand there waiting for her to wake up,” Wilkerson said.

Many locals, including Wilkerson and the late Louise Howe Bailey, referred to Sullivan as “Aunt Phoebe.”

Wilkerson shared stories of Sullivan hiring children to harvest wild plants, the elements of her curative potion. “Twelve different herbs,” Wilkerson said, “but she took the most important ingredient to her grave. Her God-given power.”

Wilkerson has in her possession the remaining drops of Sullivan’s herbal cure. Of the tiny vial, Wilkerson said, “I’m saving it for an emergency.”

Sullivan charged no fee for her treatments but accepted donations, much of which she gave away. She sponsored drives to gather food, clothing and shoes for those in need. When donations fell short, she filled in from her own pocketbook.

None of my resources ever referred to Phoebia Sullivan as a “witch,” even though she fits all of the classic descriptions of folk healers and granny witches. Her charity and close association with the church probably mitigated those fears. So, Madame Phoebia Cheek Sullivan was something of an anomaly among granny witches – a figure well-known and beloved by all members of her community. Historic Saluda goes on to say that visitors came from all over to celebrate her birthday each August, and that the streets were crowded with well-wishers.

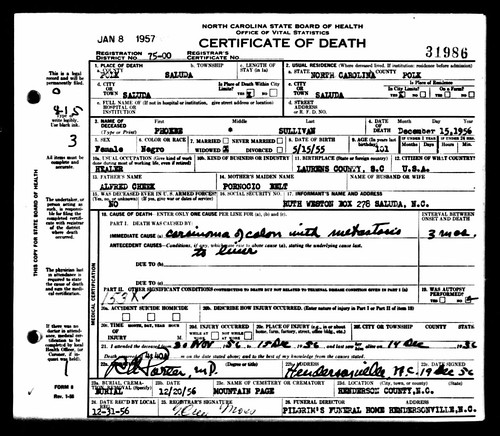

As with her date of birth, Phoebia Sullivan’s date of death seems to be in question. Historic Saluda gives her death as December 15, 1963 at the age of 99. The April 17, 1960 article in the Asheville Citizen-Times lists it as December 15, 1956. Since the article was written BEFORE Historic Saluda’s date, I’m inclined to believe it was 1956. Her listing on Find-a-Grave has the 1855-1856 dates, which would make her 101. Regardless of the discrepancy, she reached a ripe old age. There must have been something to her curative powers.

Before her death, Phoebia Sullivan dictated her memoirs as the “Book of Dreams and Visions.” The book is available online in its entirety in PDF format at the Historical Saluda website.

I think of Phoebia Smith’s reputation, and come back to my Aunt Dess. Both were devout church goers. Why does my family think of one as “conjuring” and the other as healing? Perhaps it is the source of their supposed power, skill, or whatever you want to call it. Aunt Dess supposedly got hers from pagan sources – a Cherokee woman. Phoebia Sullivan from divine inspiration. Aunt Dess is now long gone, and there are no ducks available to see if she weighs the same as a witch. Cousin Ronnie has spoken of the “Curse of Odessa” when trying to account for strange behavior in later generations of our family. At least she never turned anyone into a newt…as far as I know.

But, that’s not the end of the story. Uncle Boyce and Aunt Odessa’s house on Patton Avenue is still in the family.

A second cousin twice removed has moved into the old house and is renovating it. It will be interesting to see if either Boyce or Dess still come around to see what later generations of the family are up to.

UPDATE: Thanks to John Blythe’s diligence and investigative work, we have the definitive answer to Phoebia Sullivan’s age, birth, and death dates. John was kind enough to send me a copy of her death certificate from Henderson County.

Historic Saluda has the wrong dates. The correct dates should be 1855-1956.

Tom, my ancestors lived in the same general area as you (Gray Court / Laurens… many from Riddles Old Field / Warrior Creek). Later on, my grandparents lived not far from Yarborough’s Mill Road (although they called it “Yarbers Mill”).

Back in the day, my great uncle was known to have the gift of “talking fire”… a bit of voodoo where he could talk warts off of a person. Just wondering if, in your local travels, you’d come across the term or knew anything about the act of talking fire as I can’t seem to find anything out about it. I do remember my great uncle very well.

Still enjoying your blogs and photos!

I have heard that term, but it’s been a long time. I can’t remember if it was applied to warts, or what. It might also be good to check the Foxfire series. They had all sorts of home remedies like that.

Thanks. I’ll check that out.

Love this, Uncle Tom! Growing up I always heard the “clanging spoons story” but never had a full picture in my head of who “Dess” was! So interesting.

I truly enjoyed reading this post about your aunt. I live in the Gray Court/Hickory Tavern area on the 110 year farm where I grew up. My mother taught me folk medicine. We are descendants of Native Americans but I don’t know the tribe. We were told it was Cherokee. DNA tests revealed that I’m 24% Native American which was a surprise. I have continued to learn about and use plant medicine. I enjoyed this post because I consider myself a “granny witch”. Thank you for sharing your story!