There’s a reason I named this blog RandomConnections. The URL RandomThoughts was taken…but that’s beside the point. Time and time again the idea of “random connections” has proved itself to be the more appropriate title, as tenuous threads appear that seem to bind disparate ideas together. Such was the case this past week.

I got a forwarded e-mail from my brother, Stephen, with a note that a historical convoy would be passing through our area. The convoy would feature vintage military vehicles, and I thought it would be a cool photo opportunity. Little did I realize how closely this event would tie right into my recent research and explorations.

The convoy is sponsored by the Spirit of 45 organization, and is made up of privately owned vehicles from the Military Vehicle Preservation Association, or MVPA. I’ll speak more to their route later, but today the group had started north of Charlotte, would be stopping for lunch in Spartanburg, then traveling down Wade Hampton Boulevard and stopping at K-Mart in Greenville. They would then head to Anderson for an overnight stop. That gave me an opportunity meet them and take some photos.

Seeing the words “Wade Hampton” and “K-Mart”, I automatically assumed they would be stopping just around the corner from my house at the former K-Mart location, now a Planet Fitness and Roses. I was all set to scoot around the corner…until I took a closer look at their map on their website. They would be traveling through downtown Greenville then stopping at the K-Mart on Church Street before heading out of town. That made more sense. These guys were from out of town and would be looking for a real K-Mart…not what used to be a K-Mart.

I toyed with the idea of finding a good spot to intercept the convoy along the way, such as a high spot or bridge where I could get photos and maybe even video of them coming past. I dismissed that idea, and decided just to wait for them at the K-Mart. Since I didn’t know exactly how long it would take for them to get from their lunch stop to our location, or even when they had lunch, I figured early would be better than later. I brought my laptop and iPad along so I could get some writing done while I waited.

For a long time I thought I was the only one awaiting the convoy. A truck and a highway patrol car arrived, but they were there to discuss a hit-and-run accident that had occurred in the parking lot. The truck driver was quite upset and animated, and didn’t seem to like that I was right there watching them. Oh well.

Eventually others did start to arrive. A couple of them walked over to the patrol car and inquired, but he was just there for the accident, and had no clue. A truck pulled up next to me and asked if I was there, and I passed along what little information I had.

Soon a cluster of older men wearing VFW hats showed up. I listened to them chat a bit and reminisce about their time in World War II. Another guy showed up from the Purple Heart Association. He was in contact with the convoy, and said that they had just left Spartanburg. It would be awhile. I stayed and chatted with the vets, then waited for the group to arrive.

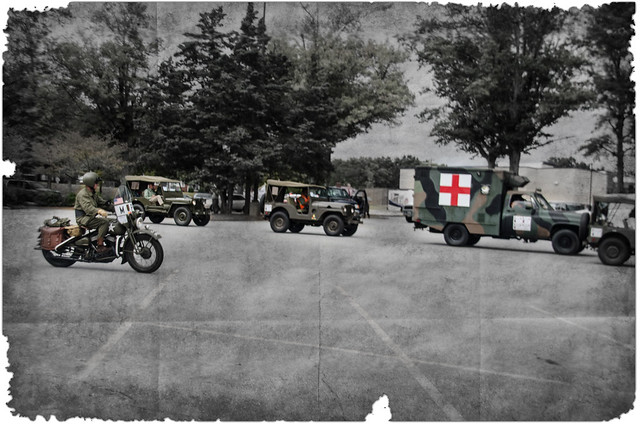

The convoy arrived about 3:45. Even though we had been waiting, their arrival caught us off guard. A military motorcycle pulled in first, followed by a jeep with a trailer. Soon all manner of vehicles were pulling into the parking lot and lining up.

They even had a half-track.

The vehicles kept coming. Mostly there were jeeps of various vintages and brands, including Willys, Jeep, and even Ford.

In addition to the jeeps there was a whole array of other vehicles, including ambulances and larger trucks.

All of these vehicles are privately owned and maintained. The individual owners are members of the MVPA. Many are retired military, but some are just enthusiasts. As with re-enactments of other types, wearing bits of the costume seemed to be the way to go.

There were also several support vehicles such as a couple of RVs. In addition, some of the owners had modified their vehicles, or at least had added trailers with camping and living gear to support their trek. I chatted with several of the drivers.

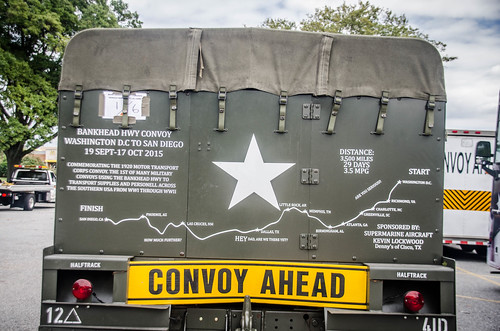

It was here that I found the random connection to my research. I spoke with one couple, Lamar and Jewell, who told me that the convoy is recreating another historic convoy from 1920. The convoy was following the route of the Bankhead Highway, one of the traditional auto trails in the early part of the 20th Century.

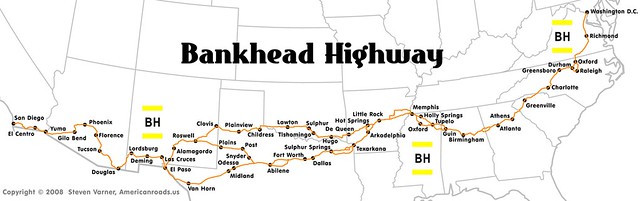

John Hollis Bankhead was a US Senator in the early 1900s from Alabama, and one of the early proponents of the Good Roads Movement. Bankhead was instrumental in passing the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, which formalized many of the early auto trails such as the Lincoln Highway and Dixie Highway.

Like the Lincoln Highway, the Bankhead Highway was a major east-west route. While the Lincoln Highway traveled through the northern states, the Bankhead Highway took a more southerly route.

Mile Zero was a marker on the Ellipse on the National Mall behind the White House in Washington DC.

A convoy had been launched in 1919 along the Lincoln Highway. At that launch a ceremony was held at the Zero Milestone in which then Secretary of War Newton Baker made the following comments:

This is the beginning of a new era. The world war was a war of motor transport. It was a war of movement, especially in the later stages, when the practically stationary position of the armies was changed to meet the new conditions. There seemed to be a never ending stream of transports moving along the white roads of France.

One of the remarkable and entirely new developments of the war was the inauguration of a regular timetable and schedule for these trucks. In the daytime they were held in thickly wooded sections, but at night each one started out with a map and regular schedule which was as closely followed as the modern railroad. In no previous war had motor transportation developed to such an extent.

It was on that spot in 1920 that another military convoy, an “Army motor train,” was launched to travel the Bankhead Highway. These convoys were more than just ceremonial. These were meant to highlight the strategic importance of a good highway system. At the launch of the 1920 convoy General Drake of the Motor Transport Corps gave the reasons for the convoy:

[To] assist in the development of a system of national highways by bringing before the public in an educational way the necessity for such a system; to provide extended field service in connection with the training of officers and men in motor transportation; to recruit personnel for the various branches of the army; to secure data on road conditions throughout the territory in the immediate vicinity of the highway along which the convoy will operate; and to secure data relative to the operation and maintenance of motor vehicles.

The American Roads website has extensive information about the Bankhead Highway. It includes a 1921 history of Alabama, Bankhead’s home state, by historian Thomas MacAdory Owen.

The War Department sent a U. S. Army Convoy over the route during 1920 thus giving government recognition to the Bankhead Highway, definitely establishing it as the most important Southern transcontinental route. The Convoy, following an impressive ceremony at Zero Milestone on June 14th, left Washington, D. C. with Col. John F. Franklin, U. S. Army, as expeditionary commander, and J. A. Rountree, Secretary of the Bankhead National Highway Association as field director, under appointment of the War Department and by the Association as representative and spokesman. The convoy was composed of forty-four trucks, four of which were 10 ton size, seven automobiles and four motorcycles. The personnel consisted of twenty officers and one hundred and sixty enlisted men. The convoy landed in Los Angeles October 6th, after traveling 4,000 miles.

The convoy received an ovation from the start to the finish. In every city, town and village through which it passed receptions with banquets, barbecues and chicken dinners were served. Public meetings were held and the people addressed by members of the convoy during which a half million people heard the gospel of good roads. It is the present expectation of the promoters of the route that the Bankhead Highway will be one of the first highways to be taken over by the Federal Government as one of its transcontinental post and military roads.

These early convoys on the Lincoln Highway and Bankhead Highway made an impression on a young participant, none other than future General and President, but then Captain Dwight D. Eisenhower. He was a tank commander, and joined the Lincoln Highway convoy in Maryland. At that time the trip was arduous, often on roads that weren’t even paved. The convoy had to stop several times to rebuilt or shore up bridges that couldn’t support the weight of the military vehicles. The vehicles themselves suffered breakdowns, including flat tires, broken axles, and other mechanical problems. All along the route the group was met by crowds, expecting speeches and a big event. Between the building, breakdowns, and speeches, the trip took 62 days.

Eisenhower reported the following:

Extended trips by trucks through the middle western part of the United States are impracticable until roads are improved, and then only a light truck should be used on long hauls. Through the eastern part of the United States the truck can be efficiently used in the Military Service, especially in problems involving a haul of approximately a hundred miles, which could be negotiated by light trucks in one day.

It was this early experience that ultimately led to Eisenhower’s support of the Interstate system during his presidency.

But, back to our convoy…

It seemed that our modern convoy was suffering from some of the same problems as Eisenhower. While the roads were in much, much better shape, these antique vehicles were still prone to breakdowns. In the K-Mart parking lot several had overheated engines, and others had hoods open checking out various problems.

Such a convoy was as much an oddity in 1920 as it is to us today. They may not have had to stop and wait for speeches, but there would be onlookers and other interested parties at each stop and all along the route.

Finally, these antique vehicles have none of the comforts of today’s SUVs and automobiles. There’s no air conditioning, no safety features, and these were built for utility more than comfort. Add to that the fact that these MVPA members are often senior citizens, and not young soldiers. While it might be fun to ride in one of these jeeps for awhile, a 3200 mile trip is going to be VERY uncomfortable.

The route this modern convoy is taking follows the original Bankhead Highway route as closely as possible. The Tobacco Trail I’ve been following through South Carolina follows one highway – US 301. That’s not the case with the Bankhead Highway. I’d thought it followed US 29, which it does for part of its route through South Carolina. However, US 29 has changed. For example, the Church Street Bridge wasn’t built until the late 1950s. It once came down Main Street of Greenville and followed Grove Road down to Piedmont and Williamston. That’s the route the MVPA convoy would take.

The Bankhead Highway took a somewhat twisting route. In April of this past year Ernest Everett Blevins gave a presentation at the South Carolina Historic Preservation Conference sponsored by the South Carolina Department of Archives & History. In addition to a history of the highway and the Good Roads Movement, Blevins described the route through South Carolina in detail.

Where is the Bankhead Highway?

Some of the Roads in South Carolina

- Grover, North Carolina

- US 29

- Blacksburg, South Carolina

- US 29/East Cherokee Street

- Gaffney, South Carolina

- US 29/Old Georgia Road

- Cowpens, South Carolina

- US 29/Main Street

- Spartanburg, South Carolina

- US 29/East Main Street

- US 29/West Main

- Vanderbilt

- US 29/W.O. Ezell Boulevard

- Spartanburg Highway

- Duncan, South Carolina

- Old Spartanburg Road

- South Carolina Highway 290

- Greer, South Carolina

- Rutherford Road/SC-23-21

- South Carolina Highway 101 and 290

- Depot Street

- Greenville, South Carolina

- Rutherford Road

- Dixie Highway/Poinsett Highway/Buncombe

- Anderson Street/Anderson Road

- Anderson, South Carolina

- South Carolina Highway 81

- Greenville Street

- Shockley Ferry Road

- Hartwell, Georgia

Once the engines had cooled down and the folks in the convoy had a chance to catch their breath, it was time to move on. The route would take them through Piedmont, Williamston, and on to Anderson where they would spend the night on the balloon launch field. I wondered if they would bivouac or stay in a motel. I’m guessing the former to be as authentic as possible.

One of these days I’m going to have to try to trace the Bankhead Highway through South Carolina. However, I’ve still got a large portion of the Tobacco Trail yet to do. The Bankhead will still be there, and it’s even closer to home.