You have died of dysentery.

That was the sad fate that awaited many who played the 1980s game “The Oregon Trail.” It was a frustrating game, and I used to enjoy torturing my students with it back in the day. The game was supposed to be a representation of the perils of pioneer life on the early cross-country routes like the Santa Fe, Cumberland, Oregon, Mormon, and Chisholm Trails.

Flash forward 75 to a hundred years or so. Railroads crossed the country, but routes for automobiles were still a challenge. Neither the roads nor the cars themselves were suited for long cross-country road trips. While one probably wasn’t going to succumb to dysentery, flat tires, steep hills, winding treacherous roads, and all manner of other problems awaited.

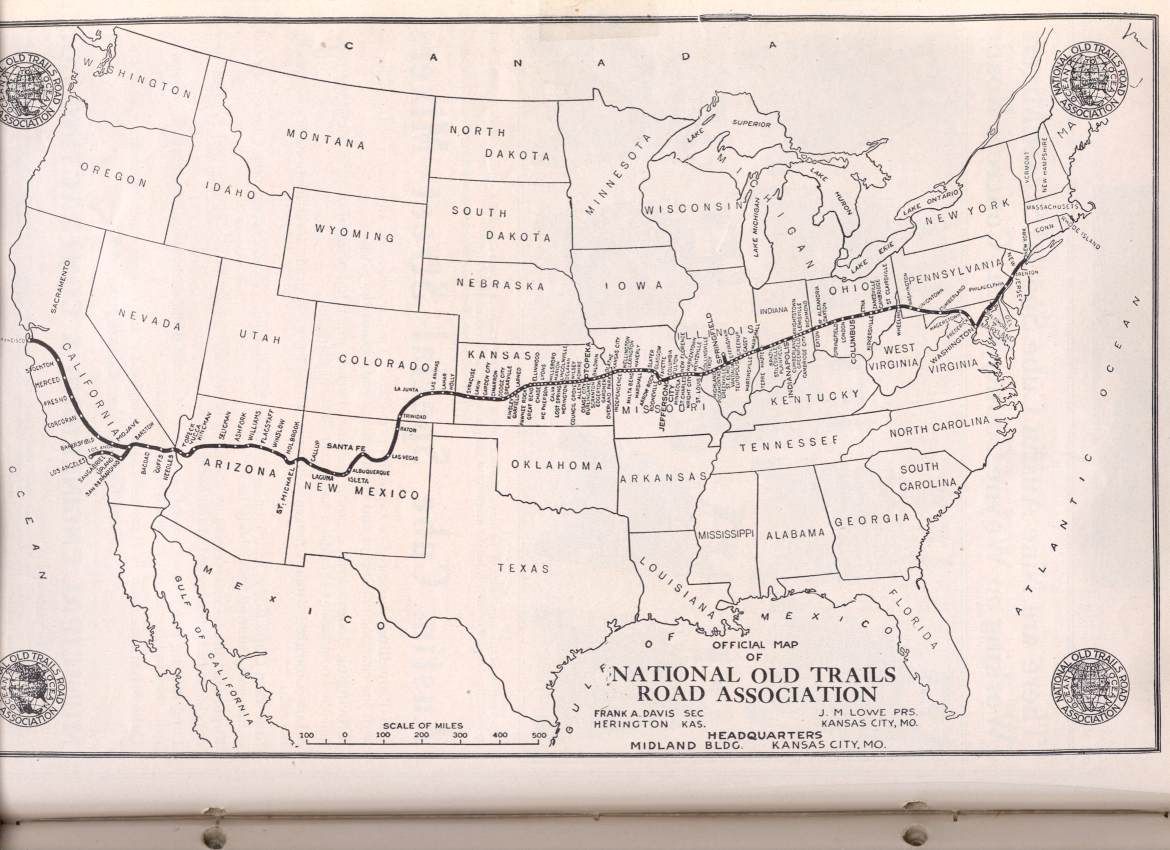

Several associations were formed to promote development of highways and improving existing roads. The National Old Trails Road Association was one of the first, and in 1912 developed a cross-continental route from New York to Los Angeles, roughly following some of the old wagon trails such as the Santa Fe Trail. Western portions of the route became the basis for part of US Route 66.

“National old trails association-usdotmap“. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

Future president Harry Truman even served as president of the association, starting in 1926.

About the same time as the National Old Trails Road was getting started, a competing route was taking a more northerly path. The Lincoln Highway was dedicated on October 31, 1913, and connected Times Square, New York, with Lincoln Park in San Francisco. This route also connected with Chicago and later added a loop down to Denver.

“LH-Map-75” by Unknown – 1916-Lincoln Highway Route-1916 Official Road Guide. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

The Lincoln Highway Association seemed to be more successful in promoting their route. At least, the notion of the Lincoln Highway lasted longer. Indiana businessman Carl Fisher, famed for developing the Indianapolis Speedway, was the visionary behind this highway. Even though the National Old Trails Road was dedicated earlier, the Lincoln highway gets the nod as the first trans-continental highway. In 1913 NPR’s “All Things Considered” did a story for the centennial of the highway.

In Robert Seigal’s interview with Kay Shelton, current president of the Lincoln Highway Association, one very important point was that the Lincoln Highway was “not a highway construction project — it wasn’t about building a brand new roadway — but rather a route-making process.”

“The Lincoln Highway’s really made up of a patchwork of already existing roads,” Shelton says. The route was intended to be the straightest possible shot between New York City and San Francisco. It was updated when newer, straighter or smoother legs were found, but Shelton says it still took about a month to get across the country.

The various roads that made up the route for the Lincoln Highway were marked with a red, white, and blue poster that was affixed to telephone poles.

The National Old Trails Road and the Lincoln Highway weren’t the only auto trails established during this time. Following the Lincoln Highway model, most of these had nothing to do with road construction or improvement, but were more about promoting businesses along said route. Usually there was an association set up for the auto trail, and travel businesses such as motels, restaurants and service stations along that trail would pay dues to the association. They would in turn benefit from being included in brochures and other advertisements from the association.

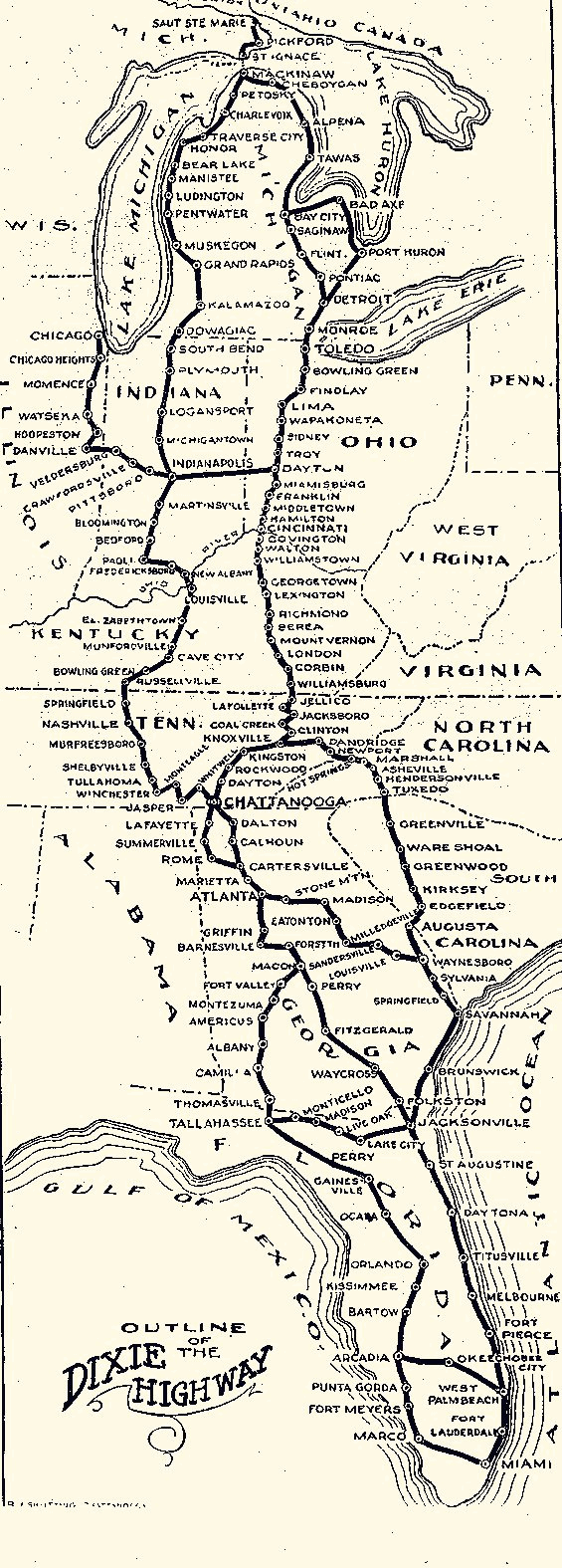

The Dixie Highway was another Carl Fisher creation, and consisted of two routes running north-south from Chicago and other Mid-west cities to Miami. The eastern route through South Carolina includes what is now US 25. Like the Lincoln Highway, telephone pole signs marked the route.

The Jefferson Highway connected Winnepeg, Manitoba with New Orleans, and the Ozark Trail was another east-west route. The Jefferson Highway still has an active promotional association.

The problem with these promotional associations was that they were more about the businesses along the routes, and less about improving the roads themselves. While this was a concern of some of the movers and shakers behind the associations, it wasn’t the overall goal. States were left to make improvements, but there was no consistency.

An article by Richard Weingroff for the Federal Highway Administration describes the problem.

In the early days of the automobile era, the named trail associations provided a valuable service. But as the number of named trails increased, and as the number of automobiles increased, so did the problems caused by the routes. Many named trails served little transportation need (the George Washington National Highway from Savannah to Seattle) or were routed through dues paying cities rather than the shortest, best route for motorists. The Dixie Highway illustrated the problem. It was actually a Dixie Highway System of alternative routes, on the theory that motorists could drive to Miami on one route, return home on another, and still be on the Dixie Highway. The Arrowhead Trail from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles, to cite just one other example, was favored by the State of Utah because the Arrowhead kept Los Angeles-bound motorists in Utah for hundreds of miles more–desolate miles though they were–than the more famous Lincoln Highway.

Rivalries among trail boosters left motorists uncertain of which route to take. In Kansas, for example, motorists could choose between the New Santa Fe Trail (backed by a trail association formed in 1910 to promote a road along the course of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad through the State) or the Old Santa Fe Trail (backed by an association formed in 1911 to support a trail roughly following the historic trade route of the 19th century). Or perhaps the motorist might want to cross Kansas on the Atlantic-Pacific Highway, the National Old Trails Road, the National Roosevelt Midland Trail, the Pikes Peak Ocean to Ocean Highway, the Union Pacific Highway, or the Victory Highway, each of which overlapped one of its rivals for part of the trip.

The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921 laid the groundwork for fixing the problem. One of the first issues was standardization of signage. Weingroff describes the situation as follows:

…Throughout the early years of the automobile era, important messages were conveyed to motorists in whatever way struck the fancy of the messenger. (One 40-foot sign in Tennessee warned motorists: DRIVE SLOW–DANGEROUS AS THE DEVIL.) Railroad-highway crossings, one of the greatest dangers of these early days, inspired the most creativity, with a skull-and-crossbones a favored warning (‘DANGER GO SLO,” a typical sign read).

At a 1924 conference, delegates and members of the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) recommended the now familiar set of shapes for stop signs, yield signs, and so on.

By 1926 the U. S. Highway System was approved. General rules were that the routes had to be interstate in nature, and with certain exceptions, had to be non-toll routes. Like the previous auto trails, the new federal highways initially followed existing routes and incorporated state highways. Improvements were made, but there was inconsistency state-to-state. The system didn’t establish minimum design standards. That didn’t come until much later with the 1956 Interstate Highway Act.

The new federal highways were marked with a shield and were numbered, with east-west routes given even numbers, and north-south routes odd numbers. Lower numbers were in the east, starting with US 1, which runs from Maine to Key West.

Even with the new federal highway system in place, many of the old auto trail associations persisted. It was a practical way to promote business along a well-traveled route. Often the association would include the new federal route name with the traditional name, especially if that federal route ran for much of the old auto trail. However, some of the long trails, such as the original Lincoln Highway, were distributed across several numbered routes. The Lincoln Highway follows US 30 fairly closely, but switches to US 50 in Salt Lake City. Probably the most famous of these was US 66 from Chicago to Los Angeles.

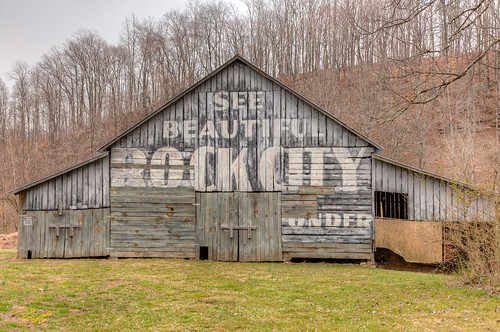

Some of these auto trail associations are still around, as evidenced by links to active websites earlier in this post. While the purpose of most of these associations is still to promote commerce along their routes, most have taken on a historic flavor, with an eye toward recognizing and preserving some of the old landmarks and tourist traps along the original roads – landmarks that were largely left to decay as Interstates bypassed cities and the traditional tourist routes.

Cool!