I was out and about exploring the Pee Dee region of the state, searching for ghost towns. I’d already found a couple of potentials – Ella’s Grove, Centenary, and Eulonia – and I’d stopped by the Marion County Museum and had lunch on Main Street in Marion. Now it was on to a couple more remote locations, and eventually find my way back home.

Myrtle Beach is a cancer. As its popularity has increased, the traffic and tackiness has metastasized onto the major arteries leading to the coast. OK, so that is a bit harsh. I’ve had some fun times there. But that’s the way it seemed to as I drove through the communities of Rains and Aynor. First up is Sparky’s, a truly tacky gift shop and the last place (or first) to snag a souvenir from the beach. There are no less than three “official” Myrtle Beach visitors centers along this stretch, and the entirety of Highway 501 is plastered with billboards advertising the latest Dolly Parton production, Pirates.

I crossed the Little Pee Dee and entered the the historic community of Gallivants Ferry. Normally I’d stop here and look longingly at the landing, wishing I could put a kayak in the water. This time I didn’t stop, but took the next right southward onto Pee Dee Road. I drove through many miles of farmland. Mostly there were peas, but there was still the occasional field of tobacco with a forlorn tobacco barn.

Jordanville

I found out about Jordanville through a historic survey of Horry County. The study indicated several buildings in Jordanville that might qualify for listing. I figured that if there were that many, the area bore checking out.

Carolana.com shows that there was a post office here starting in 1937. The website doesn’t list an ending date, but I certainly didn’t see a post office when I arrived. What I did find was an old warehouse/store, another store across the street, a Masonic hall, and a collapsed building at an intersection. The more modern of the two stores looked like it was now home to some religious organization.

So what attracted the attention of the NRHP? This is a description of the proposed historic district from the survey:

Located near the western edge of the county by the swamps fed by Little Pee Dee River, at the junction of Secondary Roads 99 and 24, Jordanville (Sites 0148) is a former crossroads community. Richard Jordan began a store at the site in 1869, which George Holliday (1875-1941) purchased in 1910. Holliday was a wealthy landowner, tobacco farmer and businessman, with property in Galivants Ferry and in Floral Beach, later named Surfside Beach. Some of the buildings he owned now form a National Register district in Galivants Ferry, which is several miles north of Jordanville (Utterback and Utterback 1988:site form; Lewis 1998:82; Bartos and Jaeger 2000). Thirteen buildings comprise the proposed Jordanville Historic District, including two homes, one store, and ten agricultural buildings, which vary from sheds to barns and warehouses, most of which likely date to the 1940s. While one of the two residences and its surrounding barns are likely still occupied, and the former store now houses a church, Jordanville is essentially an abandoned site. The largest conglomeration of agricultural, commercial, and residential buildings found in rural parts of the survey area, Jordanville is a relatively intact example of a crossroads community dating back to the nineteenth century. One home and three small outbuildings at the northern edge of the district were destroyed or removed sometime between 1988 and 2006, but their absence does not diminish the integrity of the complex.

So it wasn’t really a town, per se. Like Ella’s Grove, there was no municipal structure. Apart from the store cum church, there is a Jordanville Church and at one time there was a school here. A 1960 issue of the Florence News features an interview with a former teacher and principal from the school. However, the school shows up in neither the GNIS database nor the SC School Insurance Collection.

Spring Branch

I had a couple of choices for my return route. I could take a southern route through Lake City and cover some unknown territory, or I could backtrack a bit and hit a couple of spots north of Marion, then return a more quicker way on I-20. I decided on the quicker route.

I bypassed Marion on US 501 north of town. This turns out to be a large four-lane divided highway that connects with I-20. My GPS led me just off of the highway into the Spring Branch community. I spotted an old brick church to my left and an older wood frame Greek Revival structure across the street. This was the old building for Spring Branch Baptist. A newer version of the church was just down the road.

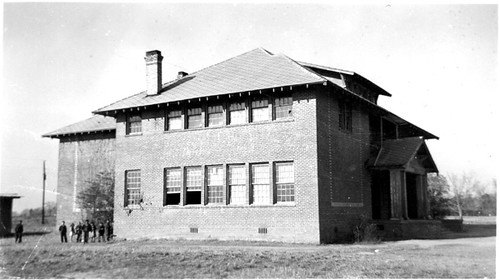

I knew there was an old school around here somewhere. I circled the block and found that if I had turned left instead of right I would have spotted it immediately. The brick two-story structure was sitting on the other side of the brick church.

I was able to find a photo of the school in the School Insurance Photos.

Back on 501 and just around the corner from Spring Branch I found another old school. There had been a Rosenwald School in the community. This was replaced with an Equalization school.

Not too far from Spring Branch is the old Ebenezer Church. This was yet another wood frame Greek Revival structure. There were two entrances, both with red doors. Lutheran? There was a cemetery, but I did not get out to explore. After all, it was one of the hottest days of the year.

I drove from Ebenezer straight on into the town of Latta. As with Marion, it would have been easy to get distracted by the history of the area. Road construction forced a detour away from the downtown area, otherwise I might have had to explore a bit more. The Dillon County Museum also would have been an interesting stop, but didn’t seem to be open.

The last two targets I decided to pursue were northwest of Latta.

Dalcho

These two targets were across the street from each other just before reaching the I-20 overpass. Catfish Baptist Church is…you guessed it, a wood frame Greek Revival structure. This places the building in the late 1800’s, specifically 1883. The building is on the National Register of Historic Places.

After reading the entry on the SC NRHP website I wish I had taken a bit more time to explore. The portico was added in 1970, but the arched entryway sounds quite interesting.

The façade consists of a centrally placed, stilted arch entrance with two, four-panel sliding doors which become recessed into the wall when opened.

Across the street was the true prize (for me, at least.) GNIS data had this listed Dalcho High School. It certainly looked like an old school. The two-story brick structure looked very ornate, and also looked like it had been converted into a private residence.

When I first saw the school it looked like there probably had been more windows on the front.

I did finally find a photo of the school in the School Insurance Photos. This one clearly shows the building as it is now, so there were no more windows on the front of the building.

There was a Rosenwald School to serve the segregated black students of the community. I also found the “Dalcho Colored School” in the archives.

Both of the Dalcho schools were involved in some controversy. The case of Tucker v Blease went to the South Carolina Supreme Court in 1914 and dealt with the question of what percentage of “Negro” blood must be present to require a student to attend a segregated school. I was able to find a summary of the case…

Being identified as a “negro” or as being in any way “colored” had drastic practical consequences back then, as yet another South Carolina Supreme Court decision reveals.

Tucker v. Blease was an action brought directly to the Supreme Court in its original jurisdiction — that is, without having to go before a lower court first. It sought review of a decision of the State Board of Education expelling several children from a whites-only public school in Marion County because of their race.

John Kirby was the son of Big John Godbolt. Godbolt was one-eighth African and seven-eighths European. That meant Big John was “colored” as a matter of law, as the law was written in those days. Like racial purity laws of Nazi Germany not many years later, one-eighth of the unwanted blood was the cutoff.

John Kirby’s mother was white. That meant that John Kirby and his siblings had less than one-eighth African blood and, as a consequence, these children were not “colored” under then existing law. Instead, having only one thirty-second (1/32) African blood, they were legally “white.”

One thirty-second (1/32) John Kirby grew up and married to a white woman. They had some children, all of whom were 1/64th African and of 63/64th European extraction.

The Kirby family all attended Catfish Church, an all-white congregation of mostly Baptists. They all had reputations of being decent people. The children were all well behaved in church and school. John Kirby owned more than 300 acres of land in Dillon County, making him eligible to vote without having to pass a literacy test.

Kirby’s family, economic and community status notwithstanding, John Kirby was guilty of a serious social faux pas. From time to time, he associated with “colored” people and allowed his children to do so too.

For reasons left unknown in the South Carolina Supreme Court’s opinion, John Kirby has been killed by a man named Edwards. The killer had a brother named Sam. After Kirby’s slaying, Sam Edwards carried a petition around the neighborhood saying that the Kirby children were not “clear blooded” and should be expelled from the white school they had otherwise peacefully attended for several years. Based on that petition, the Kirby children were kicked out of the school….

… the decision concluded that if the local white community wanted to kick the Kirby kids out of their school, it was all right with the court, albeit with a suggestion that other accommodations be made for the children’s education. As it turned out, those were “colored” schools funded at seven cents to the dollar compared to the school they had been attending.

Not a good day for South Carolina jurisprudence, helping cement the “One Drop Rule” for Jim Crow laws. The summary above says that the schools were in Marion County, but this is incorrect. They were in Dillon, which had only just formed as a county from part of Marion in 1910.

Apart from the schools and Catfish Creek Church there were several other references to the Dalcho Community in local news articles. Most of these were in reference to the Dalcho Masonic Lodge, which was one of the most active in the county. That lodge eventually moved to Latta. I could find no reference to a post office or any other commercial endeavor in the community, so Dalcho won’t make it onto my list of ghost towns.

Further exploration was tempting. It wasn’t that late in the afternoon. However, I had a long drive back that I had to take into consideration. I’d visited some interesting places in the Pee Dee region and gathered more information on South Carolina Ghost Towns. However, all this trip did was whet my appetite to delve deeper into the region. It may have to wait until our return from the west coast, but I will be back, next time not only with cameras but with paddling gear as well.

Hi,my mom and her family lived on Davis plantation and she is the only one alive of twelve children, she is now 90yrs old.she still remembers a lot about growing up there.