It was time to plan a second Saturday paddling trip for our Lowcountry Unfiltered gang. After looking at several options on the Berkeley Blueways website, we decided on a section of northern Lake Moultrie where we could paddle part of the old Santee Canal.

The post that consistently gets the most hits on this website is the tale of our visit to the ghost town of Ferguson on Lake Marion. The history of Ferguson, as well as the history of the entire Santee-Cooper project, is closely tied to this history of the old Santee Canal. So, even before heading down to the lower part of the state I figured I should brush up on my history of the area.

A few years back for my birthday my friend Dwight Moffitt gave me a copy of the Historic Canals and Waterways of South Carolina by Robert Kapsch. That’s where I started my refresher course.

The book describes a colonial province with a problem – its largest cities are somewhat separated from the interior with no clear transportation route. Charleston is situated between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers. However, neither of those rivers penetrate very far into the interior of the state. The Santee River basin is one of the largest on the east coast, but the Santee empties into the Atlantic between Charleston and Georgetown. The Carolana website describes the Santee Delta…

The Santee River and its tributaries drained much of the South Carolina uplands but its entrance to the sea, some fifty miles nortwest of Charleston, was choked by a swampy delta and a shallow bay. From there boats had to sail to Charleston inside a broken string of barrier islands, risking shallow water and ocean rip currents.

So, in order to use the Santee as a transportation route for goods one must either take a risky trip out into the Atlantic and along the coast, or use an overland connector between the Santee and Cooper Rivers. The ideal would be a waterway that connected the two rivers so that goods could be hauled from the Upstate to Charleston completely by water.

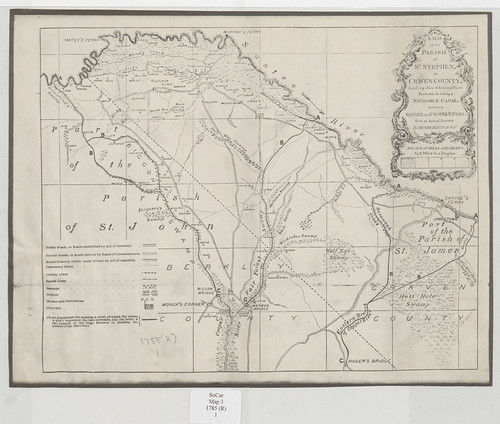

In 1773 the Colonial Assembly commissioned noted surveyor William Mouzon, Jr, to survey potential routes for a canal to connect the Santee and Cooper Rivers. He proposed five different routes across the ridge that separated the rivers.

The plans lay dormant during the Revolutionary War, but in the 1780s the idea once again gained traction. General William Moultrie was not only governor of the state, but president of the Santee Canal Company. “Subscriptions”, or stock offerings were sold to raise the capital needed to fund the project.

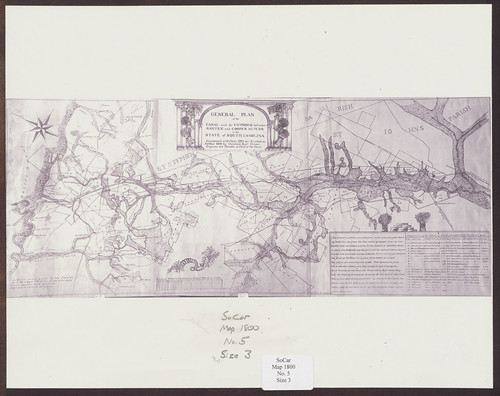

In 1793 construction began on the canal under the direction of Colonel John Christian Senf. The Santee Canal was completed in 1800. Senf’s route began at Biggin Creek, just off of the Cooper River, and ran for 22 miles to its confluence with the Santee River.

The canal was known as a “summit canal” and was the first of its kind in the US. There were ten locks, and specially designed boats carried goods through the 20-35 foot wide passageway. Of course, this being early days in South Carolina, much of the labor used to built and operate the canal was from slave labor.

The canal’s nomination form (PDF) for National Register of Historic Places designation describes the canal:

The canal route was twenty-two miles long, beginning two miles below Greenwood Swamp on the Santee River and entering the Cooper River at Stoney Landing, approximately two miles east of Moncks Corner. The canal was thirty-five feet wide at the top and five and one-half feet deep, sloping to a bottom width of twenty feet. Water depth was four feet, enabling the passage of boats fifty-four feet long and nine feet wide, weighing twenty-two tons. There were tow paths ten feet wide on both sides of the canal. The Santee Canal had a total of ten locks, tow double locks and eight single locks, which were ten feet wide and sixty feet long. With the exception of a wooden tidal lock, all the locks were made of brick and stone. The locks enabled the canal traffic to negotiate a rise of thirty-four feet from the Sante River to the canal summit and a descent of sixty-nine feet to the Cooper River. In addition to the canal itself, there were several warehouses, keepers’ houses, and other ancillary buildings along the route.

The canal began operation in 1800 and was in operation until about 1850. Problems and lack of profitability plagued the project throughout its lifetime. In 1796 during construction major floods damaged the project. Droughts from 1817-1819 had the opposite effect, but left boats stranded, especially in the highest sections of the canal. Pumps were added to make sure the dryer sections of the canal had adequate water. However, even these improvements couldn’t forestall the canal’s ultimate nemesis – the Branchville Columbia Railroad. By 1855 the canal was abandoned.

It would be another 50 years before South Carolina had is water route from Charleston to Columbia. The Santee Cooper Project begun in the 1930s created not only Lakes Moultrie and Marion, but the Tailrace and Diversion Canals connecting the lakes. The Santee-Cooper Project pretty much obliterated the old Santee Canal.

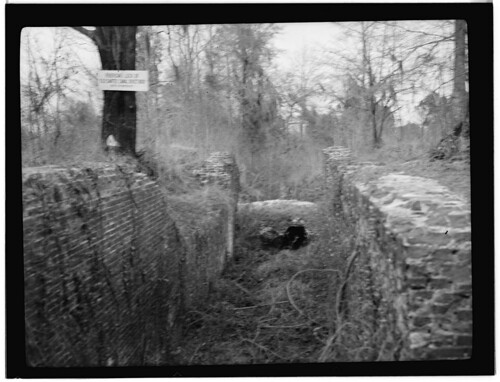

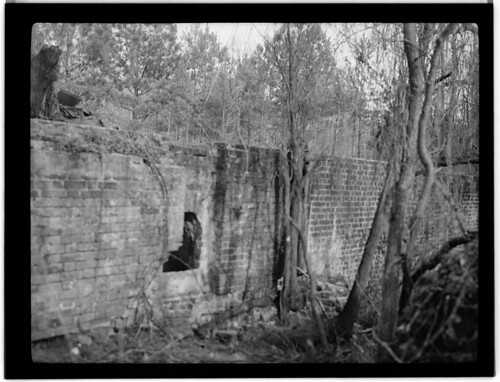

Prior to the clearing of the lake basins and inundation photographers documented the remains of the canal. These photos are from the Library of Congress. Here are the old Black Oak lock and the remains of the lock keeper’s house:

Frierson’s Lock was at the end of the five mile summit section of the canal, and served as headquarters for canal operations. These photos show the ruins of the lock, now under the waters of Lake Moultrie.

While all of the locks and construction related to the canal were either destroyed or inundated by Lake Moultrie, some remnants of the canal itself remain. The southern section of the canal starts at the Old Santee Canal Park and runs north across private property, roughly paralleling the Tailrace Canal. At the north end of Lake Moutrie one can find the summit section of the canal, starting about where the Frierson Lock used to be.

My plan for the weekend was to explore both of these extant sections. I would head down early Friday and visit the Old Santee Canal Park, then on Saturday the guys from Lowcountry Unfiltered would join me for an excursion to the north part of the canal. That’s coming up in parts two and three of this adventure. Stay tuned!