Several weeks ago I spent some time searching for remnants of the Swamp Rabbit Railroad. This isn’t the famous one in Greenville that later became a popular trail. Instead, it’s a line constructed by the Ohio River and Charleston Railroad to serve textile communities in the Upstate. Despite ambitious plans, it was only completed from Blacksburg down through Cherokee Falls, then over to Gaffney. The railroad was short-lived, but in the early 1970s the section from Blacksburg to Cherokee Falls found new life as a scenic railroad for a bit. That, too failed, and now the railroad is abandoned.

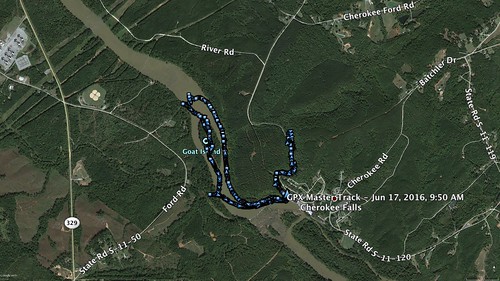

I had explored as much as I could by land. Google Earth indicated the existence of a couple of supports for the old railroad trestle in the Broad River, but I couldn’t get close enough to see them. The trestle crossed Goat Island, which also figures prominently in the story of the Swamp Rabbit. This past week Alan Russell and I were able to get out on the water, and visit these locations.

First, a bit of background…

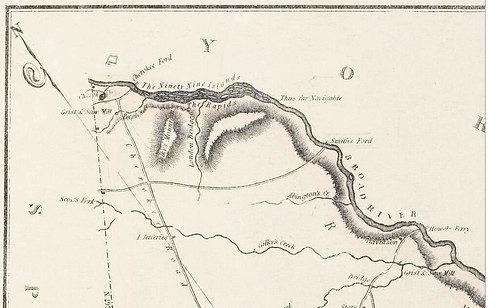

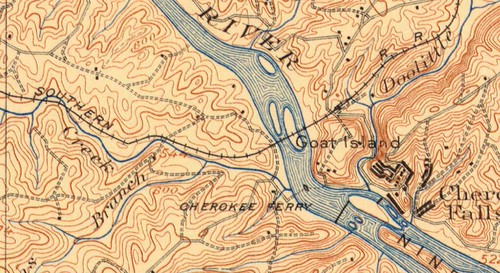

Even before the railroad this was an important transportation route. Just north of Goat Island is Cherokee Ford, a shallow crossing first used by Native Americans, and later by settlers. In 1780, the Overmountain Men from the hills of Tennessee crossed the Broad River at Cherokee Ford prior to the Battle of Kings Mountain. The location is now part of the Overmountain Victory Trail.

On the east side of the river, just below Cherokee Ford was the location of Coopersville, a ghost town that was home to the Nesbitt Iron Works. The town doesn’t appear on Robert Mill’s 1825 map of the area, and by the 1850s operations had ceased at the iron works. That only leaves a 25 year span in which it was in operation.

Even so, the Coopersville works included a canal to divert water from the river and several large buildings for the production of iron right on the banks of the Broad.

As for Goat Island, according to “A Record and History of the Peeler Family,” the island itself was home to the Peeler family, stating that, “Isaac’s [Peeler’s] home place was at Peeler Island, now known as Goat Island.” Isaac Peeler died in 1877, and most likely he was the last to live on the island. Apparently some of Isaac’s livestock remained on the island, because by the 1880s the only inhabitants were goats, giving the island its new name. A July 8, 1906 edition of the Gaffney Ledger states that the railroad removed goats from the island during construction of the Swamp Rabbit.

The Ohio River and Charleston Railroad used the island as a spot to build its trestle across the Broad River. It also recognized the potential for the island for recreation and developed facilities for the community. According to an article by historian Dr. Bobby Moss in an October 15, 1997 edition of the Gaffney Ledger…

The Ohio River and Charleston Railroad Company’s Cherokee Park on Upper Goat Island…opened on the 16th of June 1898 to the public. The opening of the Cherokee Park was a most auspicious occasion, not only for the O. R. & C Railroad, but for Cherokee County. This gift from the railroad was immediately recognized as one of the most attractive picnic grounds in the state.

On opening day, the company ran excursion trains from Blacksburg and Gaffney to the park and the fare for the round trip was 20 cents. In opening exercises, Maj. John F. Jones, on behalf of the railroad, presented the park ot the public for use as a meeting place and pleasure ground and a representative of the county, on behalf of the public, accepted.

Moss goes on the describe the facilities on the island:

The railroad company had built a comfortable landing and stairs on the trestle so that trains could stop and passengers embark and descend to the park. For the convenience of those who arrived at the riverside by private conveyances, the railroad had floored the train trestle form bank to bank. Seats had been erected all over the island for the comfort of those who wished to sit and rest themselves after promenading or dancing in the pavilion. Pleasure boats had been put on the river, and a refreshment stand had been erected where soda water, ice cream, cigars, cigarettes, etc., were offered for sale for the convenience of the pleasure seekers. In addition, swings and seesaws had been erected for the enjoyment of the little folks.

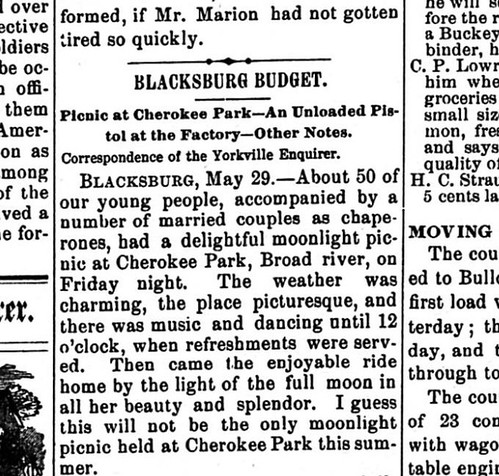

It sounds like Goat Island was the place to be in Cherokee County. There were numerous announcements in local papers about picnics, political rallies, and other meetings held at Cherokee Park. Many of them were similar to this one found in an August 13, 1898 edition of the Yorkville Enquirer:

A general picnic will be given at Cherokee Park one week from tomorrow. It is proposed to invite the candidates for county offices to present and make speeches. The Gaffney Orchestra will be on hand to furnish music for the dancers.

..and this one from 1899, also in the Yorkville Enquirer.

Alas, the fate of Cherokee Park was tied to the railroad. When the railroad went out of business and the trestle burned, the facilities on Goat Island also fell into disuse and ruin. By 1906 the Gaffney Ledger described the island this way:

The pavilion has since gone to ruin and the steps leading from the trestle to the ground has [sic] fallen away. The undergrowth is apparently only occupied by goats, while the frequent high waters of the Broad continue to cut into the island, almost dividing it in two.

Jean Vaughn Cannon operated a scenic railroad along the old Swamp Rabbit route from Blacksburg to Cherokee Falls from 1970-1971. Cannon first proposed a partnership with the Cherokee Historical and Preservation Society (CHAPS).

The B&CF Railroad hopes to be closely associated with CHAPS, Inc., since we both wish to restore some of the state’s beautiful past. The Society plans to restore Cooperville [sic], the one-time iron capital of South Carolina. This town is located at the end of the line, across Broad River. Another attraction is Goat Island located between the end of the line and Cooperville, in the middle of the Broad River.

In his proposal, he also described plans for rebuilding the trestle and revitalizing Cherokee Park. He stated that, “In our plans, Goat Island is to be built again into a giant amusement park with a picnic area and selected other items to add to the enjoyment of the B&CF RR passengers.” Cannon had been park superintendent for Echo Valley in Cleveland, SC, which featured the other Swamp Rabbit Railroad. Perhaps he had visions of turning Goat Island into a similar endeavor. Cannon’s plans also proved too ambitious. His B&CF RR was only in operation for one year before declaring bankruptcy, and the plans for the island were never realized.

So, that brings us up to the present..

With so much history in the area, I knew we had to get a closer look at Goat Island and Cherokee Ford. I picked up Alan, and we first stopped for our traditional pre-paddle breakfast…

…then drove on over to Cherokee Falls. Near the dam and textile mill is a rough river access area. I hesitate to call it a boat ramp, because I certainly wouldn’t want to back a vehicle down the hill, and I wasn’t even sure if it was really available to the public. Danger signs and concertina wire just beyond lent a definite “Stay Away!” vibe to the area. Even so, we unloaded the boats and parked the truck out of the way.

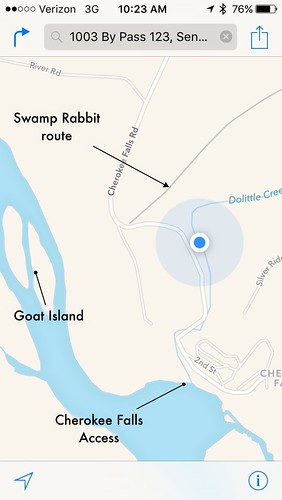

We launched at the confluence of Doolittle Creek with the Broad River, just above the Cherokee Falls dam. Since the Swamp Rabbit had run along much of Doolittle Creek for its route to Blacksburg, we decide to paddle up the creek for a bit.

The creek was wide with a gentle current. We had no problem making our way upstream. The banks were fairly rocky and steep, though. We had to jump one small limb, but were able to continue upstream under the Cherokee Falls bridge.

The creek paralleled the road for much of this stretch. We kept an eye out for any evidence of the old railroad, but didn’t really spot anything.

Finally the creek choked down to the point where we couldn’t continue. We parked the boats and continued on foot.

Along the way I found what might have been a piece of pottery. Of course, it could also be just an oddly shaped rock.

We weren’t seeing any signs of the railroad. Before continuing further I decided to check our location on my phone. I found that Doolittle Creek doesn’t really cross the railroad until much, much further upstream. While we both enjoy exploring small creeks, we were wasting our time if we were hunting for the railroad, and we had other targets for the day.

We headed back to the boats and paddled on downstream and back past our put-in spot.

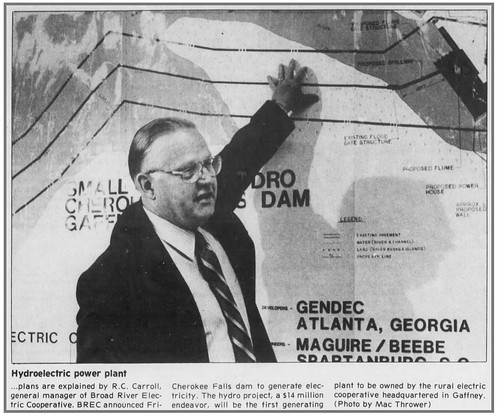

The creek enters the river right about the dam. This once marked the site of a set of steep shoals on the river, hence the name “Cherokee Falls.” The river was dammed to provide power for the textile mill, and later to generate electricity for the community. The generators lay dormant after the mill closed, but the facility was refurbished in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and is now operated by Broad River Electric Cooperative.

The old textile mill now serves as a distribution center for a fireworks company.

As we entered the main channel of the river, it was a bit… unnerving. There were warning signs everywhere, and there was a bit of a current. It wasn’t too strong, but it was more than I would have thought for a “lake” behind a dam. Most disconcerting, though, was the precipitous drop just a couple of hundred feet downstream, protected by a rickety wooden barrier running along the top of the dam.

A pontoon boat was skirting along the edge of the dam. Workers on the boat were patching the wooden barrier with pieces of plywood. It wasn’t really reassuring. The workers gave us a glance, like we were crazy.

As we rounded the confluence with Doolittle Creek we hugged the point closer than we might have otherwise. Not only was there a current, but a brisk wind. The water was also much more shallow than I would have thought. This dam has been here a long time, and I guess lots of silt has built up behind it.

As we rounded the point the current and wind picked up, but not beyond what we could handle. More importantly, Goat Island came into view. We could easily see the old trestle supports on either side of the island.

My plan was to paddle up the east channel first. This would have been the path that got the most traffic over to the island across the trestle from the mill village. We would try to paddle up to Cherokee Ford, then come down the west bank, looking for signs of Coopersville. At some point we would land on the island itself to explore.

As we paddled up the east channel, the old support loomed closer. I was hoping to get a very close look by taking advantage of the eddy behind the structure. What I wasn’t expecting was the amount of silt that had built up behind it. I ran aground quite a few yards back from the support, and had to seek deeper water closer to the mainland.

Only two trestle supports were visible in Google Earth – one on either side of the island. We discovered that there were actually many more. On this side of the river there was the central one that was was visible in GE, but there were supports on either side of the channel, as well.

Most maps show Goat Island as two separate islands with a central channel. I’m sure that at one point it was a single island that was split by the river. The island was in two sections when the railroad was built, as old maps show the crossing between both islands. GNIS data has the name pinned to the west island, but it’s most likely that Cherokee Park was on the east island.

At the north end of the eastern island was a long sand spit, which obscured the entrance to the channel between the two islands.

The wind was really against us as we continued upstream. Eventually I reached the first rock shelf of the small shoals at Cherokee Ford. These shoals are fairly shallow, and I could see how horses might have crossed here.

The current was also much stronger right below the shoals. I used a ferrying move to make my way across to the west bank of the river. I was at the location of Coopersville, as far as I could tell, still slightly upstream from Goat Island. From the banks we couldn’t see any of the structures that might have been at the iron works site. The remains are supposed to consist of foundations and old canal works, which probably wouldn’t be visible from this angle, anyway. Plus, I think the actual remains were a bit further upstream, into shoals that would be a challenge. The banks were steep, and as we were contemplating whether or not to explore on foot, a dog started barking at us from the next residence down. We decided to continue on.

Alan and I turned down the central channel between the two main islands and beached the boats on the sand bar. We scrambled up onto the island and found ourselves in thick underbrush with lots of briars. The thought of hacking my way through this southward wasn’t very appealing.

Instead, we descended to the sandbar on the other side of the point. Walking was MUCH easier. We made our way downstream with no problem, discovering in the process that we were actually on a smaller, third island separated by a narrow channel.

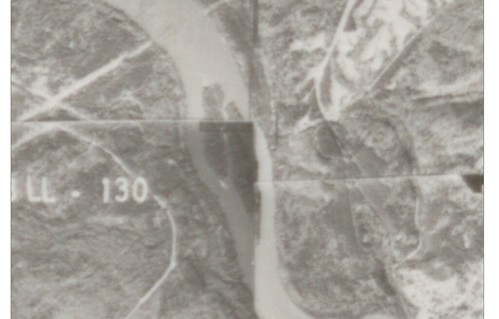

I checked the Google Earth archives, and it looks like this third island existed as far back as 1994. Google Maps shows only two islands. I’m sure when water levels are low this actually is two islands instead of three. Going back further, aerial photography archives show that the interior channels changed over time. In this 1970 photo, the third island looks like part of the western island, rather than the eastern. The images at the USC collection go back to 1941, and they all show three islands, not two. As time and current altered the landscape, if there were any remains of the old park in this area, they would have been long gone.

As we walked back to the boats we spotted some interesting footprints. There were some HUGE heron prints…

…something that looked like Bigfoot had been here…

…and the tracks of something that looked like it had been scurrying around, possibly hunting.

Back in the boats we continued down the middle channel. Ahead were two more trestle supports. We were now up to five confirmed – three in the east channel, and these two in the middle channel. We pulled up to the support on the west side of this channel and pulled out our boats to explore even more.

Getting onto the west island was a challenge. The banks were steep, and I stepped out into deep silt, causing me to lose balance for a moment. Fortunately I didn’t take a dive. At the top of the bank we found more undergrowth, and fewer briars. We could also see three remaining supports on the other side of the island in the same configuration as the ones in the east channel. There were eight trestle supports in all.

It quickly became apparent that the only evidence of the park we might find were these supports. It’s just been too long for wooden structures to have survived. We made our way back to the boats.

Large thunderclouds had been popping up around us all morning. The radar app on my phone showed storms around us, but we were OK for the time being. Even so, I didn’t want to take too many chances. We headed on back toward Cherokee Falls.

We took one more side detour. Peeples Creek enters the Broad River above the dam from the west. We decided to check it out. An ibis guarded the entrance. We didn’t venture too far, though. The creek was trashy, the water nasty, and not navigable beyond about 50 yards.

Heading back it was good to have the wind and current behind us this time. I’d always rather have wind and tide/current behind me on the return trip. We once again passed the rickety wooden superstructure of the dam. I described it to Laura later, and she suspects that it’s to prevent larger debris, such as logs, from sweeping over the dam and perhaps damaging it. While it wouldn’t be a pleasant experience, at least I had the assurance that these boards should prevent me from going over the dam, if I got too close. I still didn’t risk it.

We pulled up to the ramp in time to see a very threatening cloud. However, like all the others this morning, it, too, passed us by without dumping rain. We were able to load up the boats safely.

We drove through Cherokee Falls so that Alan could check out the mill village, and found ourselves headed toward Blacksburg. We turned left onto US 29, and I immediately knew there was a problem. There were several semis in the eastbound lane at the traffic light where we turned, and traffic continued to back up. Fortunately for us, the westbound lane was clear. We found out later that a truck had jack-knifed on the interstate and traffic was being routed on 29.

I told Alan that a good day’s paddling starts with breakfast and ends with barbeque. We had a late lunch at Daddy Joe’s BBQ to round out the adventure.

In all, we paddled/hiked 4.43 miles, which is more than I expected. The Doolittle Creek excursion added more to the trip than my estimate for the day had been. We didn’t find any artifacts, but it was still a cool, historical place to visit.

Finally, here’s a link to all of the photos from that album. It was a good day exploring, but I think I’m done chasing swamp rabbits.

Hey, thanks so much for all of the details and photos of your trip to Peeler/Goat Island. My 4th great-grandfather is Isaac Peeler who lived on the island. I have been researching him and his family for years and have wondered what his home area looks like. I’m quite amazed that I found such a detailed account of the river he lived on. I wish you could have a show on The Travel Channel. Thanks for your desire to find evidence of the railroad not knowing that you were helping a descendant of Isaac Peeler who lives in Texas!

I thoroughly enjoyed the photos and details of your excursion to Goat Island on the Broad River at Cherokee Falls, , this has been very informative. I’ve always been interested in that area, thank you so much !