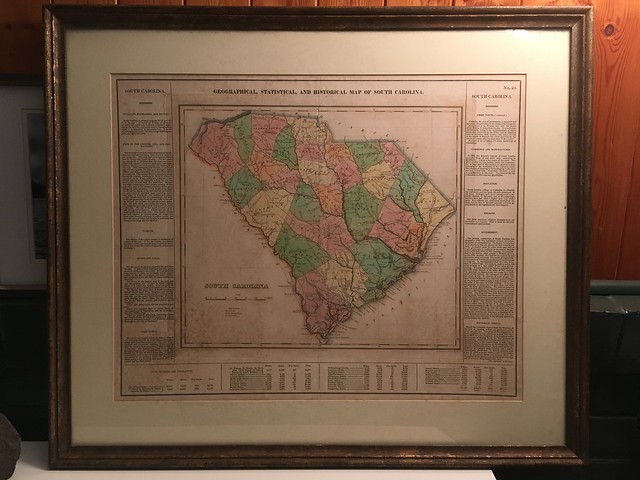

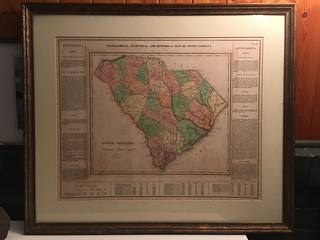

I recently acquired a map from my Aunt Grace’s estate. While she was in Paris she found an old map of South Carolina in an antique store. The map had lots of interesting information, including the slave population for each county. The information and history intrigued her, and since it was from her home state, she bought it. Aunt Grace knew that I was a map geek and was especially interested in the history of the state. Before she died she expressed her desire that I get the map. I won’t go into the long and sordid details of how it did eventually end up in my possession, but rather delve into the history of the map itself and the cartographers that created this work of art.

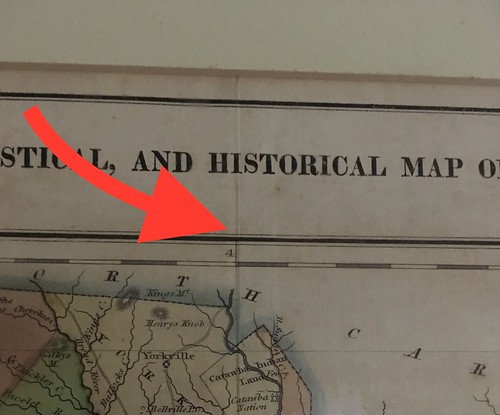

Of course I wanted to know more about this map. When was it published? Is it authentic? (And, secondarily, what might it be worth?) The information on slave populations indicates that it was pre-Civil War. I used other context clues from the the map and was able to do a Google image search. After doing a bit of digging I found that this map was from a much larger atlas published by the firm of Carey & Lea of Philadelphia in 1822. The complete title of the work is A Complete Historical, Chronological and Geographical American Atlas, being A Guide to the History of North and South America, and the West Indies: Exhibiting an Accurate Account of the Discovery, Settlement, and Progress of Their Various Kingdoms, States and Provinces, together with the Wars, Celebrated Battles and Remarkable Events, to the year 1822. Whew!

A complete version of the atlas is available online from the David Rumsey Collection. In that collection is the map of South Carolina.

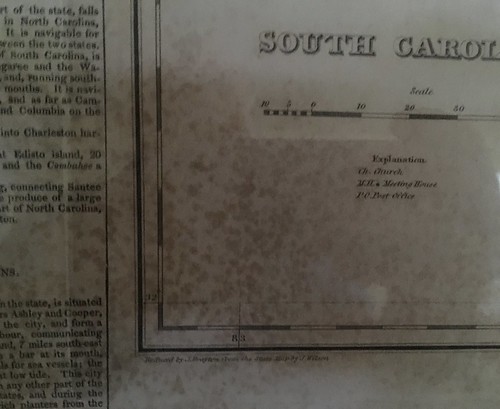

From the bibliographical information found on the David Rumsey site I learned that this map was printed in 1822 and that it was created by John Drayton, based on a prior map by John Wilson. Samuel Huffy was the engraver. Now I had several names to track down. Doing so led me to a host of fascinating men, each with their own intriguing stories.

First up is the family of Mathew Carey. Carey was born in Dublin in 1760 and got into the publishing business at the age of 17. It seems that he also enjoyed publishing his own political works, and ran afoul of the British government. He fled to Paris where he met ambassador Benjamin Franklin. Carey came to the US with Franklin and work with him in his publishing firm, making friends with John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and other political leaders of the day.

Carey established his own publishing firm in Philadelphia and continued to publish his own political works, as well as works by Sir. Walter Scott and James Fenimore Cooper. He was an ardent supporter of the nascent country, and that support tended to permeate all of his publications.

Carey eventually turned over his company to his son, Henry Edward, and his son-in-law Isaac Lea. After the elder Carey’s death the publishing firm became known as Carey & Lea. On a side note, the Wikipedia entry for Isaac Lea describes him as “an American conchologist, geologist, and publisher.” Lea’s son, Matthew Carey Lea, was a lawyer and chemist who delved into early photography. As I said, these were fascinating people

The younger generation’s support of the United States was just as strong as the elder Carey’s’ Isaac Lea even fought in the War of 1812. This support showed up in many of their publications, including maps.

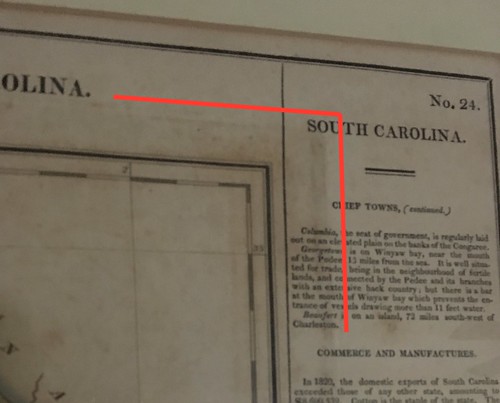

Maps can be strong political statements. Labels, boundary lines, and just about any other detail can be used to enhance or diminish a particular region. When Carey & Lea created their atlas of the western hemisphere they followed the pattern of an earlier French map maker, Emmanuel-Augustin-Dieudonné-Joseph, comte de Las Cases, more commonly known as “Le Sage.” La Sage was one of the first to use the margins around the map to include additional, almost encyclopedic information about the region. Carey & Lea used this same process, but also included text and information generally favorable to the states.

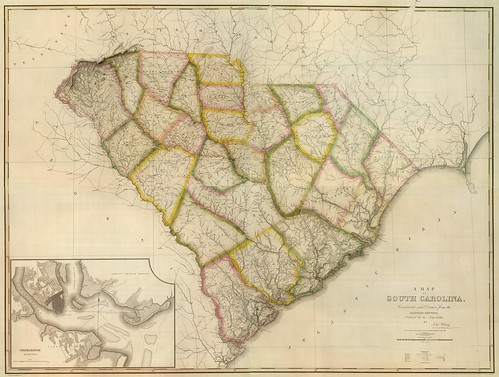

As for the South Carolina map, the entry in Carey & Lea’s atlas is attributed to John Drayton. I haven’t been able to find any additional information on him, but as far as I know this is not the John Drayton of Drayton Hall fame, though he may be related. Drayton’s map was based on an earlier map by John Wilson, “late Civil and Military Engineer of South Carolina” according to the engraving on Wilson’s map. Wilson’s map was also published in 1822, but by a different firm owned by H. S. Tanner. It is also available in the Rumsey collection.

Drayton is listed as the author of the map listed in the Carey and Lea atlas and Samuel Hufty is credited as the engraver. The map had to be engraved in reverse – mirror imaged. Then it was stamped in black ink on a blank sheet and hand colored. There could be subtle variations in each printing and shading. The sheet was then sent back through the printing press to add the borders and text.

As for the additional text around the map, I’m unsure of the source. However, it seems reasonable to think that if Carey & Lea outsourced individual map production to local sources, then the same might be true of the text. In keeping with the idea of promoting the states, much of the language on the map is quite positive. For example, the opening sentence of the paragraph describing the geography starts like this:

The sea-coast is bordered with a fine chain of islands, between which and the shore this is convenient navigation.

Not everything on the map is complimentary, though. I found the description of the climate of South Carolina particularly amusing.

The climate of the upper country is healthy at all season of the year. In the low country the summer months are sickly, particularly August and September; and at this season the climate frequently proves fatal to strangers.

There is a section listing “Civil Divisions and Population.” The population includes the number of whites, slaves, and free blacks. In the lowcountry districts the number of slaves often outnumber the number of whites by a wide margin. For example, Georgetown has 1830 whites listed, but 15,546 slaves and 227 free blacks. Conversely, Pendleton district has 22,140 whites and 4715 slaves.

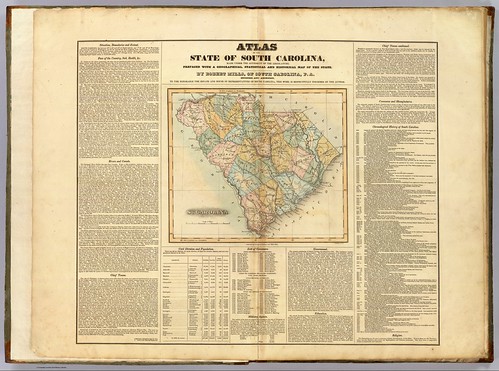

I’ve come to rely on the 1825 Robert Mills Atlas of South Carolina when I’m checking out historical areas of the state. The Wilson and Drayton maps predate this by a couple of years, but realistically they were probably in development about the same time. Even so, it’s interesting to compare the Mills maps with these. Since Mills focused solely on South Carolina with individual maps of each district, his maps have much more detail.

That covers the history and creation of this map of South Carolina, but what about the authenticity and value of my particular map? I haven’t taken it to be appraised, but there are some things I can tell about it.

First, I’m pretty sure that it is an authentic map and not a reproduction. There is a crease down the center of the map. Normally this wouldn’t be a good thing, but in this case it’s evidence that the map was taken from a larger bound folio.

Around the central map the engraver’s mark is clearly visible. This would have been from the initial map imprint, with the text added later.

I found an excerpt from an episode of Antiques Roadshow that discusses the map of Missouri from the Carey & Lee atlas. The expert, David Cresswell, discusses the center crease as well as the stamp marks.

So the map is probably authentic. What about value? The PBS show originally aired in 2000 and gave a value of $600 – $700 for the map. This excerpt was rebroadcast in 2015 and gave an updated value of $1500.

I tried looking online at auction houses, rare map dealers, eBay, and other resources. I found prices for Carey & Lea maps ranging from $125 to $800. I didn’t find the $1500 the Antiques Roadshow indicated. This was from a mix of state maps and I don’t know if certain states carry more value than others. I did find one complete Carey & Lea atlas where the asking price was $14,500.

I wouldn’t be able to assign a true value to my map until I get it appraised. While 1822 was the first edition of the atlas, there were seven subsequent printings. The maps on the David Rumsey site are scanned from an 1823 printing. There’s no way to know from which of these editions this map comes. There are also some condition issues with the map. In a couple of the corners there is some spotting that may be from mildew damage, etc. I’m sure that would affect the value of the map.

As for me, though, I don’t really care. Unless this thing is fantastically expensive and insurance costs prohibitive, I’ll just hang onto it. It has more interest and value to me as both a historical and sentimental artifact.

The map is fascinating, and I am grateful to Aunt Grace for remembering me. I would also like to thank my cousins Charles Mayo and Mim Burton and my sister Glynda for seeing that the map did get to me. Their help is greatly appreciated.

Awesome!!! Do you know how much it might be worth? I wish I could stumble across a find like that.