My latest historical obsession has been the Mountain Lily, a steamboat that plied the waters of the French Broad River between Brevard and Hendersonville. I’d been able to dig up a bit of information about the boat, but now it was time for a photo trek to see what evidence and remnants remained of the ill-fated boat.

Joining me on this expedition would be Jim Leavell – history professor emeritus, photographer, and fellow kayaker. I had created a map of possible targets based on my research, and this would serve as the basis for our trek.

We wanted to explore some of the access points along the French Broad, but I really wanted to visit the Henderson County Museum to see their display on the riverboat service.

We headed out mid-morning last Thursday to Hendersonville for our first stop, the Henderson County Heritage Museum. The museum is housed in the old county courthouse on the main street of Hendersonville.

In the years since my retirement I’ve had the privilege of visiting lots of local history museums. The quality varies, but more often than not I’m impressed with what these organizations are able to do, often with limited resources and budgets. Henderson County has done an outstanding job with their museum. There were displays of militaria, local commerce, and settlement of the area, which seem to be common to most of these museums.

The most impressive items were the models. There was a room with a complete rendition of the Saluda Grade, showing the railroad all the way from Tryon through Saluda and on to Hendersonville. The detail was amazing and it really gave you a feel for that piece of railroad history.

Sadly, the museum had a strict “No Photography” policy so I wasn’t able to get any photos of these marvelous displays. This presented a problem, because I really wanted to get shots of their model of the Mountain Lily. Sometimes, though, all you have to do is ask. Museum supervisor Eric Gilliland and docent Lynn Herrick graciously allowed me to take photos of the Mountain Lily display when we described our project and research. They were also very helpful with additional information.

The display was small. The original sign from the riverboat hung over images of Col. S. V. Pickens and the steamboat in its heyday.

There was a framed sepia print of the Mountain Lily run aground near Kings Bridge, which seems to be the one I found on just about every online resource. Below that was my main target, the model of the Mountain Lily.

As with the other model work in the museum, this was done in stunning detail. It showed the original colors, white with green trim, and the wooden lattice work covering the side paddle wheels. It looked like a beautiful boat, albeit a bit tall and unwieldy. I took photos from all angles.

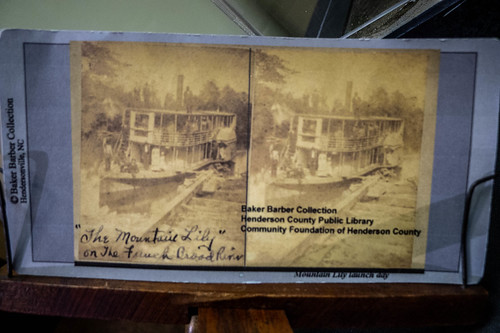

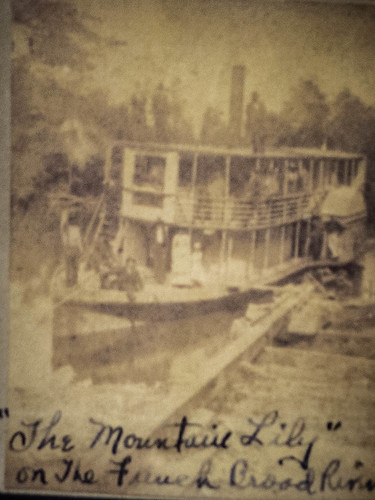

Sitting on top of the model display case was a stereoptic viewer. The card inside had a view of the Mountain Lily that I’d not seen in any online resource. This image showed the boat in operation, rather than stranded on a sand bar.

On closer inspection, this didn’t look like a real stereo card but one that was created by the museum based on a historical image. When I tried to use the viewer it didn’t render as a 3D image, which was the whole point of the viewer. Even so, it was a cool image. A black and white enlargement was on the wall under the Mountain Lily’s sign.

We thanked our hosts and I bought Terry Ruscin’s book A History of Transportation in Western North Carolina, which had additional information about the riverboat.

It was now time for lunch. Confession time. This whole Mountain Lily thing was a ruse. It was just an excuse to get me up to Hendersonville at lunch time so that I could visit Haus Heidelberg. I’ve long bemoaned the dearth of good German cuisine in our area and I didn’t find much where I was in Washington. I’d been craving a good plate of sausage, sauerkraut, hot German potato salad, perhaps a beer and apple strudel. The diet would start next week.

I was worried about Haus Heidelberg. Last winter the area was subjected to terrible flooding and the restaurant had some damage.

It looked like things had recovered, though, and there was no evidence of the flooding. The food was excellent and just as I had remembered. Sadly, their beer taps were out of order so I didn’t get my Warsteiner, and we both decided to skip the apple strudel. Maybe next time.

Our next stop was Horse Shoe First Baptist Church, the former Riverside Baptist that had used planks from the boat in construction of the church. I knew that along with the new name had come a new modern building, so the planks were probably long gone. However, the bell was supposedly intact.

We drove through farmland and rural areas north of Hendersonville. Even though I’ve driven Highway 64 many times, I’d never paid much attention to the communities lining the river – Horse Shoe, Etowah, Penrose, Blantyre. I may have to make another trek up this way just to visit those (and eat more German food.)

We found Horse Shoe First Baptist with no problem.

Under a small shelter next to a larger picnic shelter we found the bell. At least, from everything I’ve read, I think this was the bell for the Mountain Lily. There was no signage or historical marker.

It appeared to be well-maintained and in great shape. Jim had to make sure that it rang properly.

There was no visible connection between the church and the riverboat other than the unmarked bell. I couldn’t find a church website with its history. The Henderson Heritage website has the following information:

In 1888, Baptists living in the area of Horse Shoe near the post office and river formed Riverside Baptist Church. The Rev. D.B. Nelson was the first pastor. There were 29 charter members. The church first met on land near the French Broad River. In 1898, the church sold this land and purchased land from M.J. Allen. They salvaged wood and the bell from the “Mountain Lily.” They hung the ship’s bell “on posts in the churchyard and used it until 1924.” The bell is located today under a covered shelter at the church.

Having found the bell, our next target was the river itself. I had several river crossings marked that had come up in my research. Some of these were just bridges and some had access to the river. For the points with just bridges we had trouble getting a good view or photograph. Usually there was other traffic that didn’t take too kindly to traffic stopped in the middle of the bridge and the land on either end of the bridge was marked “No Trespassing.”

At the Horse Shoe Crossing there was a developed access point. There was an actual boat ramp, although I couldn’t imagine anything but johnboats and paddle craft launching from here.

North of the access was the Horse Shoe Bridge and to the south was a railroad bridge. The river was enticing and looked perfect for kayaking. It did NOT look perfect for a riverboat, though, and I couldn’t imaging a boat of the size of the Mountain Lily coming through here.

Our next stop was the bridge at Blantyre. A dirt road led to a rougher launch. The wooden launch looked like it could either be a heck of a lot of fun or a total disaster.

Blantyre was of interest because this is supposedly where some of the river modifications had been made. At certain water levels you can see jetties that were designed to trap river debris and keep it out of the main channel. The water levels were fairly high on our visit and no jetties were visible from this point, but we had a secret weapon.

Jim had brought along his DJI Spark drone. The plan was to flight it down the river a bit to see if we could capture images of the jetties or any other remnant of the riverboat service. Jim got the drone ready and launched from the access point while I enjoyed the shade of the bridge.

I soon realized the flaw in our plan. First, there was lots of tree cover and it would be difficult to fly navigate through the vegetation. Adding to the difficulty, we were launching between the bridge and overhead power lines – not a good idea. Lastly, we were over water. A collision with any of these obstacles would plunge Jim’s expensive drone into the river. Caution got the better part of valor and Jim wisely brought the drone back in.

We did get a couple of good shots of the river. It just confirmed the fact that this is a narrow, shallow, twisting river and that riverboat traffic would have very difficult along here.

With the drone safely pack away we continued our trek. We took Highway 64 on into Brevard, noting other river access points at Etowah and Pisgah. My mind was racing with the number of kayaking possibilities through here. In Brevard we stopped at the Transylvania Heritage Museum.

The docent on duty at this museum were not as knowledgeable as the folks at Henderson and the displays were sparse in comparison. There was a timeline painted on the wall with a few artifacts displayed beneath. There was nothing about the Mountain Lily. Jim also noted that there was absolutely nothing about Cherokee heritage, either, or, at least, none that we saw. The information seemed a bit…one sided.

We drove back through the town and stopped for coffee on the south end of town. While sipping we looked up and saw that we were right next door to the Transylvania Visitors Center. We walked over and found them to be much more helpful than the museum. Susan, the center director, was very familiar with the Mountain Lily, but didn’t provide any additional information than what we already had. She did, however, give me an excellent map of the French Broad River showing mileage and all of the access points. I’ll definitely use this in planning future river trips.

We had one final stop. On the way out of Brevard we stopped at the Hap Simpson Park with access to the French Broad. The parking lot was somewhat flooded (large puddles, really) from recent rain and the access looked muddy, but doable. There were trees down along the stretch of the river along the road, but it looked like a kayak could get through with no problem. We continued on without taking photos.

It had been a great day out and about exploring. I was glad that Jim was able to come along with me. We found some tangible evidence of the Mountain Lily, but the next step was to experience the river itself. That meant getting out the kayaks.