The “small world syndrome” always catches me off-guard. At the Bellingham Folk Festival I met musicians that live in Asheville and frequently play in Greenville. Even just meeting someone who has visited South Carolina, much less my home town, makes me feel a connection. As I’ve found out, though, the Southern connections with the Pacific Northwest are even deeper than I had thought.

I was especially surprised when I spotted this pickup truck in Burlington…

The truck had Washington plates, so the Confederate flag sticker is inconsistent, unless the owner is a Southern transplant. Even back home such a sticker is problematic, but up here it’s really “in your face.”

But, perhaps the owner would have been right at home on Samish Island. Let’s go back to just after the time of the Civil War…

George Washington Lafayette Allen has perhaps one of the most patriotic sounding names of all time. Allen was born in Lee County, Virginia and moved to Washington State sometime in the mid-1800s, but the date seems to be in dispute. Some sources list Allen as a Confederate veteran. However, some also place him on Whidbey Island as early as the 1850s, which would preclude his fighting in the Civil War. He may or may not have been the sheriff of Island County, but he did serve at least a couple of terms as sheriff of Whatcom County, which at the time included Samish Island. Allen was also a land speculator, buying up large tracts of land on Whidbey Island, Bayview, and Samish Island.

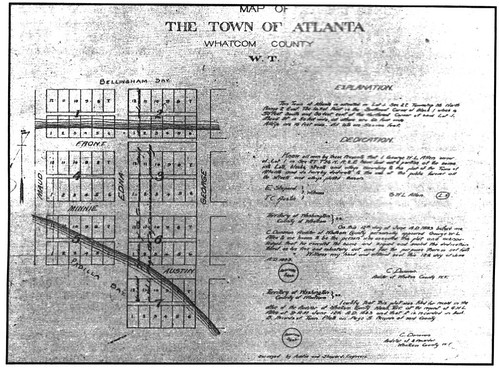

Regardless of when he arrived in Washington, Allen kept his loyalties with the the South. Allen had moved to Samish Island in 1883 and laid out a plat for a town he named Atlanta.

Allen built a dock along the island’s existing wharf and a three-story hotel overlooking Bellingham Bay which he named the Atlanta Home Hotel. Allen dedicated the town and hotel as “a sanctuary for persecuted Confederates and other sympathizers of the Lost Cause.”

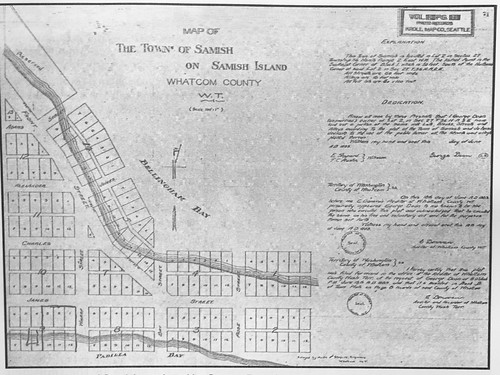

This apparently didn’t set well with Union veterans on Samish Island, and especially with landowner and Union sympathizer George Dean. The same month that Allen registered his plat for Atlanta, Dean and his neighbors registered a plat for the town of Samish just one street away from Allen’s town.

Both towns competed for steamboat traffic, including passengers and cargo. Dean extended his dock so that it would be larger than the one in Atlanta. Allen added a saloon to his town and Dean succeeded in getting a post office, each in an attempt to get more customers.

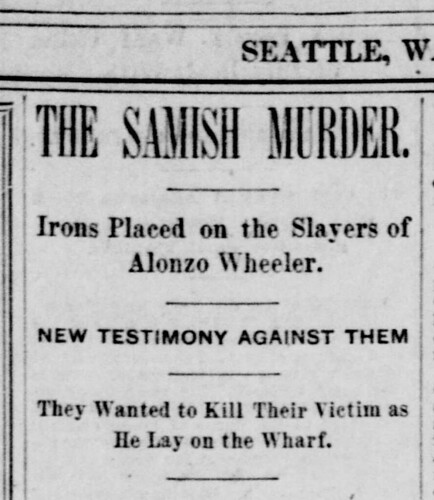

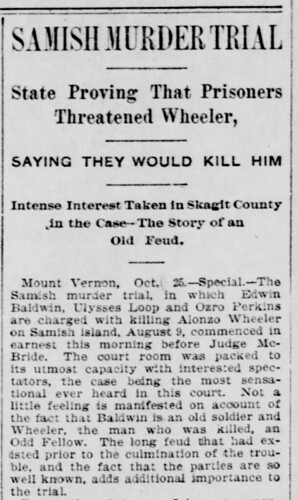

Tensions ran high between the two factions and there was occasional violence. This came to a head in 1895, resulting in the murder of Alonzo Wheeler. Wheeler, a former Confederate soldier, worked for John White who operated a service providing cordwood for steamers running between Samish Island and Edison out of Atlanta. Edwin Baldwin and Orzo Perkins had a competing service out of Samish. According to the book Samish Island History by Sue and Fred Miller, “On August 9, the two factions fought with iron pipes, guns, and cork soled boots.” Wheeler received a gunshot wound and later died in Anacortes. George Dean broke up the fight. Baldwin, Perkins, and Ulysses Loop were arrested for Wheeler’s murder.

The murder and subsequent trial was a sensational event for the region. The Seattle Intelligencer reported on the trial proceedings. The men were tried and convicted, with Baldwin receiving a ten-year sentence, Perkins five years, and Loop one year.

The towns prospered for a bit, and Atlanta was even under consideration for county seat of the new county of Skagit, also founded in 1883. Atlanta was to become another Lost Cause, though, as was its neighboring town of Samish. In the 1890s railroad lines were completed through Mount Vernon and Anacortes, linking the region from Seattle to Bellingham. Steamer traffic decreased along the Puget Sound. Neither town developed beyond the steamer services, saloon, hotel, and a couple of stores, and soon these services faded away.

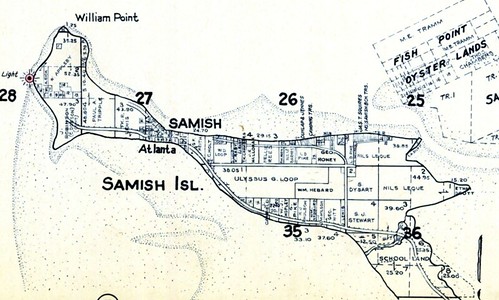

The names persisted, though. This 1941 map of the island still shows Samish and Atlanta along the narrow neck of the island. This map also shows Ulysses Loop as one of the largest land owners on the island, despite his conviction in the murder of Alonzo Wheeler.

George Allen continued to run the hotel until his death in 1903, with his family continuing for several years afterwards. When new owners took over it was renamed Lummi Lodge and continued a moderate business as the only hotel on the island for many years. According to the Miller book, “It had 2-1/2 stories, with porches off the first and second floors. The front door opened into a large lobby and then an ample dining room. A boardwalk came up form the dock and extended the length of the building.” The hotel was lively during the 1920s. In the Miller book island resident Madeleine Hopley describes the “dances held there, and her fascination at seeing cars draw up and let out the ‘flappers’.” In the early morning of January 5, 1933, the Atlanta Home Hotel, aka Lummi Lodge caught fire and burned to the ground.

As for George Washington Lafayette Allen, the man with the patriotic name and would-be Confederate rebel? His legacy is left throughout the Skagit Valley area. The community of Allen bears his name, as do Allen West Road and Avon Allen Road.

He died in 1903 on Samish Island at the age of 75 and was buried in the Bayview Community Cemetery.

Back to the present day…

With two ghost towns within walking distance from our island home I had to pay them a visit. Samish and Atlanta were located on the narrow neck of the island. Today there is no sign of the towns. There is a close collection of cottages along the neck, but even these are starting to be replaced with larger, more opulent homes as land prices on the island skyrocket.

Wharf Street is still there, along with one of the few indicators that there had been some commerce on the island. Another store building sat on the close corner, but it has since been subsumed into a much larger domicile that kind of got out of hand.

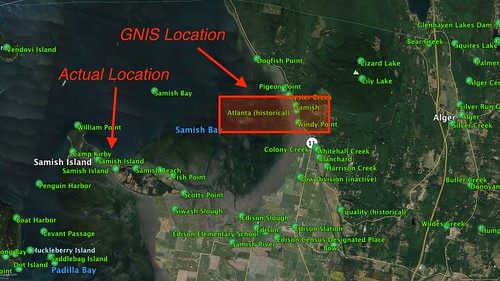

This Google Earth view shows the former location of the towns, labeled a bit more clearly and accurately than the 1941 map posted above.

I drove over to Bayview and pulled into the cemetery. I’d driven past many times without stopping, but now I had an excuse. I wanted to find George W. L. Allen.

The cemetery dates from the mid-1800s, so it wouldn’t contain any of the early funerary art or signed headstones I usually seek. There are over 1,000 graves registered, dating from those early times up to the modern era. There are a few columns and other raised monuments, but now flat stones are required.

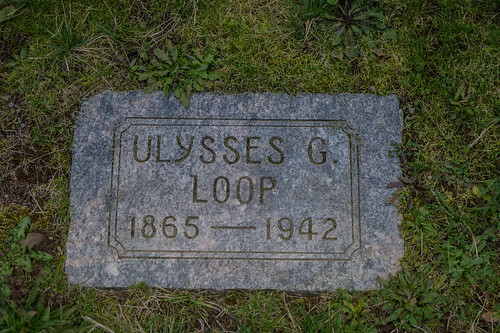

I came across the grave of Ulysses G. Loop. From the dates it looks like he would have been a young man of about 30 when he was convicted of the murder of Alonzo Wheeler.

I found the Allen monuments. There was a raised central monument with just the name “Allen” but no further inscription.

George Allen’s headstone was to the left. It was an unusual horizontal cylinder. The name inscription was mostly illegible, but had read “G. W. L. Allen”. The dates were clearly visible – 1828-1903.

To the right was another grave but I couldn’t make out a name. At first I assumed it was Allen’s wife, but the date of death is wrong. He divorced his first wife in 1862, his second wife died before he did, and the third wife outlived him and remarried.

It turns out that this was Adrian Allen, George’s son, who drowned off of Samish Point when his boat capsized in a squall.

Doing the research for this post was a challenge. First there’s the problem of George Allen himself. The Skagit County Museum has him listed as a “Confederate veteran.” However, other records show that he was on Whidbey Island in the 1850s. Unless he returned south to fight in the war it is unlikely that he was a veteran. According to the Skagit River Journal…

We have researched for several years to determine if Allen returned to his native Virginia to fight in the Civil War, but thus far we have not found any proof. He moved west in 1851 and spent most of the next two decades in Island County before he became a Padilla-area farmer, Whatcom County sheriff and town boomer. We hope that descendants of his family or researchers will help us fill in the gap of his timeline from 1860-70.

The Journal goes on to state that Allen was listed in the 1860 and 1870 Censuses for the area. Even his tenure as sheriff is unknown. His very brief obituary states that he was sheriff for ten years, but the Journal has only been able to confirm two two-year appointments.

But it’s not just a problem with G. W. L. Allen’s life events. Somehow incorrect geography has be entered into the official record. GNIS data shows the towns of Samish and Atlanta along the coast of Bellingham Bay below Chuckanut and Blanchard Mountains. This is completely wrong. This Google Earth image shows where GNIS has the locations and where I’ve marked the correct locations.

Even in Google Maps Samish shows up as a place name in the wrong place and that incorrect data has made its way into GPS data.

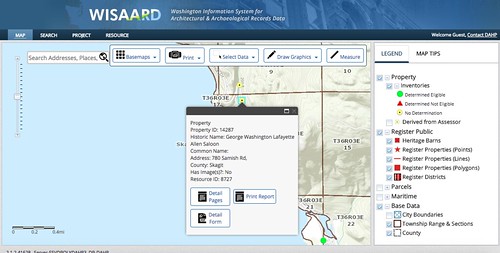

The WISAARD (Washington Information System for Architectural and Archeological Data [whew!]) also incorporates this error into their maps. Along with other properties evaluated for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places is a listing for “George Washington Lafayette Allen Saloon” at 780 Samish Road. The property has the designation “To Be Determined” meaning that it hasn’t been evaluate.

Naturally I was quite excited that there might be an extant building associated with Allen. From the location on the map I thought it might be the old Oyster Bar. I even rode up Chuckanut Drive and took a couple of photos.

The building is so heavily modified that it wouldn’t be included in the register. The restaurant’s own website says that this started as a shack built during the Depression and was expanded to its current form. That’s long after Allen’s time.

When I looked back at the actual information for the listing I spotted the address – “Samish Road.” There is no Samish Road. There is a Samish Island Road, but even 780 Samish Island Road doesn’t take you to the right place. I’m guessing that whatever algorithms WISAARD uses for geocoding just spotted “Samish” when it couldn’t locate the correct street address and matched it with the incorrect GNIS data. Very frustrating.

So that’s the tale of George Washington Lafayette Allen and his Lost Cause(s). In Part 2 I’ll take a look at some other connections between Southern states and the Pacific Northwest. Meanwhile, here are the primary references used for this article:

- Samish Island Community Website

- Skagit River Journal

- Skagit County Historical Society

- Samish Island: A History from the Beginning to the1970s by Susan and Fred Miller

- WISAARD

- Lost Communities of Skagit County

- Find-a-Grave

A very interesting story. It is frustrating when the record is wrong and there seems to never be an avenue to correct it! I have seen those round markers here in Camden and other old 1800 burial grounds.

Hello, Dennis George, from Mt. Vernon. I believe that the ‘Samish’ on the Chuckanut side was a named Great Northern RR siding. On Samish Bay of course, but not related to the Samish on Samish Island. This is where Taylor Shellfish is located.

In the woods just off my parents property in Bay View is an old small family plot of graves. One of the headstones is for “Esther, wife of GWL Allen” but we were never able to find record of her.

*my previous comment should read the name Agnes, not Esther.

Thanks.

Hi Tom,

I am a researching about Washington’s Darker history that isn’t taught in PNW History. I would love to talk with you about your research.