The recent flooding in the mid-state has pointed out some of the glaring problems with South Carolina’s infrastructure. Even before the floods, the issue of deteriorating roads has been foremost, with discussion about how to fund road repairs. This isn’t a new problem, though. The question about how to develop and maintain adequate infrastructure is not a “one and done” proposition. First there was the King’s Road and Great Wagon Road, then in the 1820s it was the development of the Santee Canal and the State Road. The development, maintenance, and funding of an adequate means of transportation was, and always will continue to be an issue.

In the last post I made a few comments about the roads around Greenville – basically trails that connected town to town. The condition of those roads was often appalling. This was true for the entire country around the turn of 20th century. The automobile was just taking off, but getting anywhere proved to be a challenge. Thus, the Good Roads Movement was born.

Genealogist Anne McCuen described the condition of Greenville roads in the 1800s, particularly in the “Dark Corner” of the county, in her book of family history entitled Including a Pile of Rocks.

Roads available to the Senter family and their neighbors, in the early 1800s in the Glass Mountain area, were simply former Indian paths widened by the use of wagons drawn by one and by the droves of sheep, cattle, hogs and turkeys. In fact, at the time, most of the roads in the entire County of Greenville could be described as such – Clark’s trail, Riken’s trail, Gowen’s trail, an the Lower, the Middle, and the Upper trails or paths.

McCuen goes on to describe the construction of the State Road through the Saluda Gap, under the supervision of Joel Poinsett. This improved things, but through the middle of the century the primary mode of long-distance transportation was still the railroad. It wasn’t until independent modes of mechanical transportation became practical that the need for better roads became apparent.

The Good Roads Movement actually predates the automobile. The first group to call for improvements in roads and highways was the League of American Wheelman, or LAW. This was actually a bicyclists’ organization, founded in Newport, Rhode Island in 1880. The organization began to lobby for better road conditions not only for cyclists, but to improve commerce as well.

Initially their impact was somewhat limited. Bicycling was seen as a largely urban gentleman’s activity. Fortunately, they were able to cultivate some allies. In the 1890s farmers began to feel isolated and dissatisfied with the rates charged by railroads for transportation of their goods. The LAW began pulling together a coalition of farmers, bicyclists, and advocates for the Rural Free Delivery postal system. The organization began publishing a “Good Roads” bulletin on a monthly basis, and also published “The Gospel of Good Roads: A Letter to the American Farmer.”

This coalition alone wasn’t able to bring about the change without better organization, though. Roads remained in poor shape until the automobile was adopted as a major form of transportation. According to the blog “The Automobile in American Life,”…

As a result of this demand for more equitable transport, the National League of Good Roads was established in 1892. The group held a convention in Washington, D.C. a year later, and subsequently in 1893 the Office of Road Inquiry was established within the U.S. Department of Agriculture. This agency, with little funding to operate adequately given the task at hand, was responsible for collecting factual data on the nation’s highway system. Its 1904 road census was most revealing. The U.S. had 2,151,570 miles of highway, of which 153,662 miles, or 7 percent, could be classified as improved. Of this total, some 38,622 had a small stone surface, 108,233 had a gravel surface, and the rest was covered with sand, shell, and even some plank. Only 141 miles of roads could be considered acceptable for vehicle traffic (particularly in the light of the unreliable and frail autos of that day) – 123 miles of brick and 18 miles of asphalt.

…Of far more significance than the political pressures of bicyclists or farmers was the appearance of the automobile. The motor vehicle added to the pressure for road improvement, and indeed was an even stronger incentive than the bicycle, since it was a lot harder to extract a car stuck in the mud than a bicycle. And the fact that the automobile was an expensive item initially motivated the most wealthy and politically powerful group of Americans in having a personal interest in the Good Highway Movement.

In the early 1900s adventurous souls were setting off on long-distance road trips in their new automobiles. Not only were bad roads a problem, but these early automobiles were subject to frequent breakdowns.

In 1908 R. H. Johnston had been attending an automobile race in Savannah, Georgia, and decided to drive back to New York by way of Atlanta. He set out in a 1908 open-air White steam-powered automobile with three associates. Along the way Johnston wrote about his travels and the roads he encountered. These were published in a 1908 edition of Travelers Magazine.

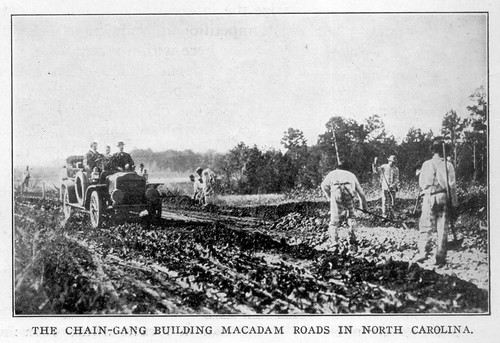

In Georgia Johnston describes a common practice of the times, using convict labor to build and improve roads.

We covered a total distance of 120 miles between Atlanta and the South Carolina boundary. Almost all of the going was over rather poor roads, alternately of clay and of heavy sand. But it is a safe prediction that, within a few years, Georgia will have a splendid system of highways, such as even now cannot be found in three or four of the counties in which large cities are located. The change is being brought about, not because of an irresistible popular sentiment for good roads, but because of the recent overthrowing of the “convict lease” system. There had developed in Georgia a system whereby the convicts were leased to “convict brokers” at a nominal sum by the several counties. The brokers, in turn, leased out the convicts to the owners of mines, brick yards and lumber camps who worked the convicts “to the limit.” As a result, a limited number of very influential citizens and officeholders benefited greatly by the system and the convicts were never sent out to work on the roads, except in three or four counties. The abuses of the “convict lease” system became so pronounced that a vigorous compaign against it was started a few months ago by an influential newspaper, The Atlanta Georgian. As a result of this campaign, the governor convened the legislature in extra session and the “convict lease” system was annihilated by statute. Therefore, there is now nothing for the convict to do but to work on the roads. If one county cannot use all of its own convicts on its own roads, it must lend them to any other county which applies for them.

Johnston went on to describe the roads that he found in South Carolina…

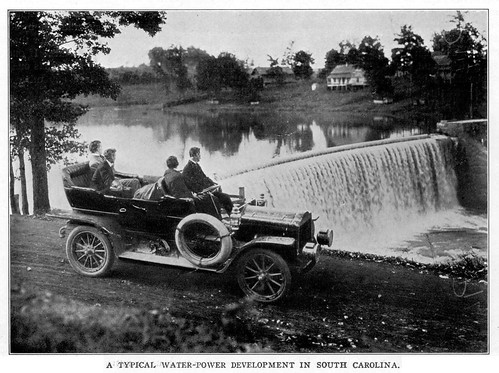

In South Carolina, we at once noticed an improvement in the character of the roads. The Georgia roads go up and down hill with most precipitous grading. In South Carolina, the roads were evidently laid out by surveyors, with the result that they wind easily up and down hill. I might say here that there is absolutely no level country between Atlanta and Roanoke. One is continuously climbing or coasting. Fortunately, the “water-break”—that formidable characteristic of the mountain roads of Pennsylvania and other northern States—has never been introduced into the South.

Anderson was the first important town we passed through in South Carolina and next we reached Greenville, a hustling city located 167 miles from Atlanta. As far as Greenville, we had been cutting “cross country” in the sense that we had not followed any line of railroad. At Greenville, we struck the main line of the Southern Railroad and for the next 150 miles, or as far as Salisbury, N. C., we were seldom very far from the main line of this road.

When Johnston reached Greenville, he made note of the early beginnings of the city as the “Textile Capital of the World.”

All the way from Atlanta we had been in a cotton country—in fact, we had seen little else being raised. The farmers’ wagons we had seen were all loaded with cotton or with cotton seed—the cotton being taken in bulk to the gins and then in bales to the towns for shipment. Starting about at Greenville, we noted a new phase of the cotton industry, namely, the cotton being made into cloth at the point of production, instead of being shipped to Fall River or to Manchester. The advent of the cotton-mill has created the “New South.” The profits of manufacturing have been kept at home and have been added to the more precarious profits of agriculture. As a result, the southern mill town shows all the evidences of prosperity to be observed in similar communities in New England.

Continuing northward through the region where “Cotton is King,” we followed the route of the Southern Railroad through Chick Springs, Duncan, Spartansburg, Gafney and Blacksburg and finally crossed the State line into North Carolina near the little town of Grover…

When Johnston reached Charlotte he made particular mention of the macadam paving. One individual with which he spoke said that “the value of farm land immediately jumps ten dollars an acre as soon as it is connected with a town by a macadam road.”

There were other such journeys. Many of these were “pathfinding” expeditions to establish routes for new national highways. Automobile associations such as AAA and the National Highways Association were also getting started, and began advocating for better roads and funding, as well as working diligently to set up the various national highways. I’ll write more about that in subsequent posts, but for now I want to stick with the conditions of the roads themselves.

The 1913-1916 annual reports from the South Carolina Agriculture Commissioner had large sections focusing on good roads, along with a county-by-county report of improvements. The 1913 report states that Charleston County had “constructed 60 miles of roads of the first class, of that kind consisting of the following: 7 1/2 miles of cement gravel, 24 miles of sand and clay, 2 1/2 miles of oyster shell and 26 miles of earth.” The 1914 report states that there were nearly 15,000 cars in the state.

There were several local bond issues to improve roads. The state agriculture reports reveal that not everyone supported spending money on roads. Even though farmers had been advocates of good roads with the League of American Wheelmen, the farmers of South Carolina weren’t as supportive. The 1919 report quotes Hampton County agriculture commissioner William Gifford as follows:

Hampton County has three great railroads running through it lengthwise, another along the southeast border, and one short line from northeast to southwest, connecting with the C. & W. C. at Hampton Court House. There are very few points in the county located more than five miles from a main line railroad station where freight and passenger trains stop regularly several times every day Every corner of the county is covered by daily mail deliveries, and the railroad postoffices [sic] receive and dispatch mail from two to four times a day…

…There is great complain by traveling salesmen, and the automobile public generally, on account of the poor condition of the highways, but the farmers and lumbermen seem to be satisfied with them; at least they are not enough dissatisfied with them to assess themselves with special taxes to improve them. The reason for this, of course, is because the hauls for the farm and forest products are very short. The great majority of farmers and saw mill operators can receive their supplies and deliver their products at railroad stations located only a mile or two from their fields or woods, and in most cases they can take their choice of shipping directly to Charleston, Columbia, Savannah, Augusta or Port Royal.

The roads are very irritating to men who use automobiles for business, but automobiling for most farmers is just a sport, and when you come to think about it there is more sport in steering a machine around pot holes and through wiggly sand ruts than in just letting it glide along a nice wide boulevard. No genuine sportsman cares to murder birds that are driven over him in flocks. He prefers to pull through bushes, stumble into holes, and over logs, and take snapshots at the quail as they whir up from under his feet and flit between tree-trunks and saplings. He grumbles all day long at the labor and danger of falling down and blowing a hole into himself, and he’s tired and worn out when evening comes, but he has the feeling of satisfaction that his bag of birds has been earned, and that each victim had a reasonable chance to get away. He remembers each one distinctly; just how it got up, just how it looked when he fired, just how it fell, and just how hard it was to find. And that’s the way with most Hampton County people about automobiles. If they simply want to go or come they ride our trains, but they rake to the automobile as a genuine big game sport which as about as much hazard in it for the rider and the machine as for the objective.

I can’t tell if Gifford is being sarcastic, or if he had a specific word count he had to reach with that hunting analogy. The state commissioner mitigates this a bit with a statement about the type of roads farmers want:

What the farmer wants and needs is a good road to his nearest market and the tendency of the last few years, emanating from our large cities, is in exactly the opposite direction. In other words, our well meaning enthusiasts have dished up a city road building program, and hence it is little wonder that the average farmer doesn’t jump up and crack his heels together for joy – for remember, the average farmer is more interest in getting a load of hogs or corn to market and in occasionally taking his family to a moving picture show in the nearest town than he is in cross country joy-riding.

The 1913 report defined the types of roads that could be found in the state as follows:

- Improved Earth Road

- Gravel Road

- Sand-Clay Road

- Oiled Macadam Road

- Bituminous Macadam Road

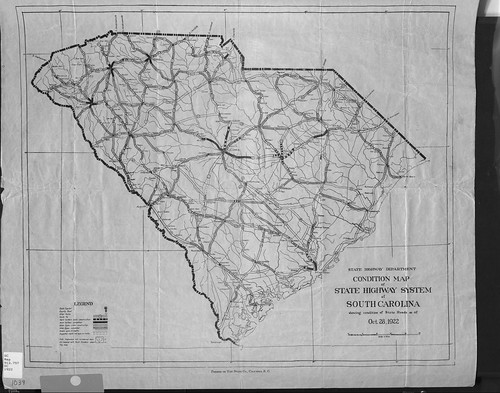

The report doesn’t describe the type of asphalt paving with which we are now familiar. This was a rarity, as were concrete roads. Even as late as 1922 roads were not in great shape in South Carolina. This 1922 map shows the condition of roads. The heavy black lines indicated hard pavement. Those are generally just around cities. The rest of the state is shown as “other,” most likely one of the types of roads described above.

Even with opposition from some farmers, road bond initiatives at the local and state level passed. The first federal funding was enacted in the form of the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916. The bill was introduced in the House by Representative Dorsey Shackleford, and in the Senate by Senator John Bankhead. Bankhead’s name would become synonymous with the Good Roads Movement, and would eventually lend itself to one of the early trans-continental highways.

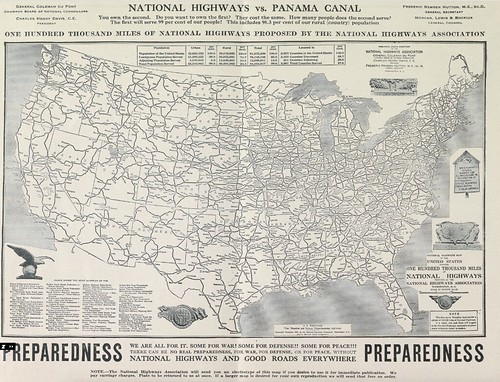

The Good Roads Movement had an unexpected boost with the advent of World War I. This was the first truly mechanized war, and it pointed out the strategic advantages of having good roads. Many publications of the time made this point. For example, in 1917 Charles Henry Davis, president of the National Highways Association addressed a meeting of the Southern Commercial Congress in New York on the importance of good roads. Davis pointed out that developing a national system of good roads was more cost effective than the Panama Canal. A map on a flyer for the conference points out the strategic importance of good roads.

Road development and improvement was well underway, but still in its infancy. The Federal Highway System and Interstate Systems were yet to come. In the next couple of posts we’ll take a look at some of the early pathfinding expeditions, we’ll look at the evolution from guide books to road maps, and look at the development of the Bankhead Highway.