In Part 1 of this series I took a look at the legacy of Edward C. Jones, a South Carolina architect who until just a few weeks ago was unknown to me. Having done a bit of research, I decided it was time to do a bit of ground-truthing. Wednesday was an absolutely spectacular fall day, despite an oncoming hurricane, so I wanted to take advantage of the weather while it held. My ramble would take me on a loop up through North Carolina then back down through Spartanburg. As usual on these rambles, I made discoveries I never intended, and met some cool people along the way.

I was much more familiar with Jones’s corpus than I had thought. There were lots of his buildings that I had already visited. Of course, I never visited Furman’s Old Main, but I certainly have lots and lots of memories of the Belltower replica that now graces Furman’s campus.

I had also visited the Church of the Holy Cross in the ghost town of Stateburg in Sumter County. This was the final resting place of statesman Joel Poinsett, who lent his name to so many places around Greenville.

I knew there was lots to see in the lower part of the state, but I didn’t have enough time to drive that far. I needed to find examples fairly close, and that meant driving up to North Carolina, oddly enough.

So why would a Charleston architect be so active way up here and in the wilds of North Carolina? This actually makes quite a bit of sense.

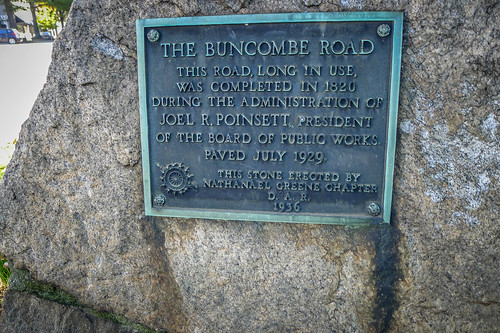

In the early 1800s a road called the Buncombe Turnpike was built between Asheville and Greenville. Remnants of this road still exist as Buncombe Road in Greenville, and a monument stands across from Buncombe Street Methodist Church.

The road was paved as a “plank road”, making it more accessible to travelers. Wealthy plantation owners from Charleston could now make the trek up to resorts in the mountains to escape the heat. The town of Flat Rock, in particular, became known as “The Little Charleston of the Mountains.” As they built their new homes in the mountains, they would want someone with whom they were familiar. So, Edward Jones became involved with several projects in Henderson County.

I got up early and drove up US 25 and took the turn onto NC 225 toward Flat Rock. My first target was another spot with which I was familiar – the Mansouri Inn, aka Woodfield Inn, aka the Farmer’s Hotel.

Mansouri Inn

Back when Laura and I were just dating this was known as the Woodfield Inn, and we came up here for dinner. The Woodfield Inn closed, but the venue re-opened as the Mansouri Inn in 2009. The inn was built as the Farmer’s Hotel in 1852 on 28 acres of rolling land at the height of Jones’s Italianate period, and the architectural touches reflect that style. Note the shallow pitch of the roof, the wide eaves, and the arches created by lattice work around the porch, and compare those to the upper windows of the Furman Belltower.

When I drove onto the property I was greeted by a deer eating apples from a tree. Other than that, I didn’t see anyone else. I wasn’t sure if the place was even still open.

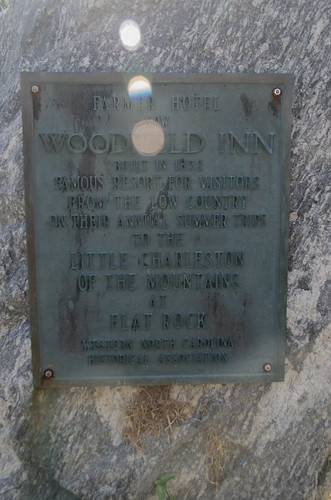

There was a marker that had obviously been built during the Woodfield days.

It was backlit by the morning sun, so I didn’t get a good image. The marker reads as follows:

Farmer Hotel

now

Woodfield Inn

Built in 1852

Famous resort for visitors

from the Low Country

on their annual summer trips

to the Little Charleston

of the Mountains

at Flat Rock

Western North Carolina

Historical Association

As I pulled out of the drive I finally spotted life around the inn. A pickup with workers was parked at the spot where I had seen the deer.

My next stop was on the other side of Flat Rock, closer to Hendersonville. It was a spot I had passed many, many times, but never stopped. Today I was finally going to stop at St. John in the Wilderness Episcopal Church.

St. John in the Wilderness

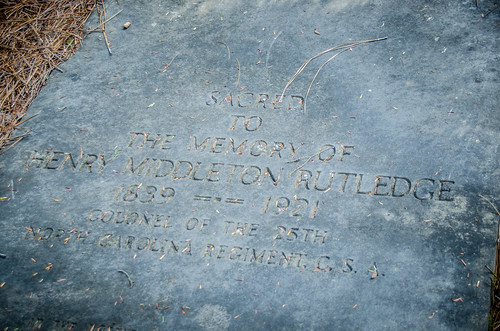

Friend and fellow explorer Keith Dover and been telling me for years that I need to visit the cemetery here. He said that many of the names located here were the surnames of famous families from Charleston, such as Pinckney, Middleton, Tradd, and Rutledge. That’s where I started my visit.

The thing that struck me were the number of Celtic and other crosses throughout the cemetery.

I was able to find some of the prominent Charleston names.

One of the most prominent was the grave of Christopher Gustavus Memminger, who served as Secretary of the Treasury for the Confederacy.

As you might expect with a cemetery full of prominent Charlestonians, there were a couple of signature stones. W. T. White made an appearance, along with a new name to me – “A M & M.”

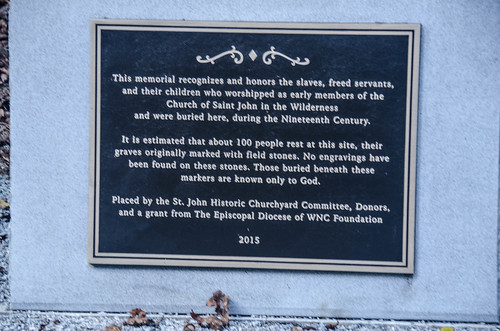

On the other end of the socio-economic spectrum, one part of the cemetery was set aside for the slaves and freedmen who work on the Charlestonians’ homes and who also worshipped at St. John.

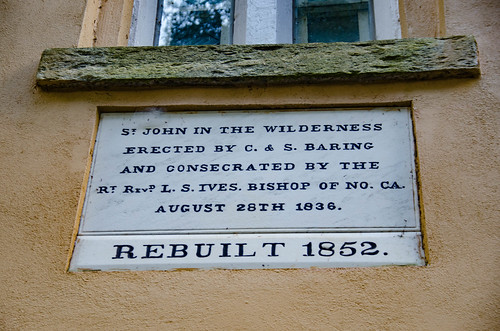

While the cemetery was cool (quite literally this fall morning), I was here to look at the church architecture. St. John in the Wilderness started as a private chapel of ease in 1838. In 1852 Edward Jones was tasked with enlarging the church and adding the bell tower, the same year he was working on nearby Farmer’s Hotel. It was very difficult to get a clear photo of the building because of all the trees.

The tower looked very similar to Furman’s, with the shallow cap and arched windows.

There were some workers painting the wrought ironwork around the family plots. I asked the sexton about the possibility of seeing the interior, and he welcomed me. I headed on inside.

The interior was stunning, with plaster walls and dark wooden beams that reminded me of Fourth Presbyterian in Greenville. The seats were box pews, similar to St. Philips in Charleston. The pipe organ console was near the front with one small rank of pipes, but the bulk of the pipes were at the rear of the church.

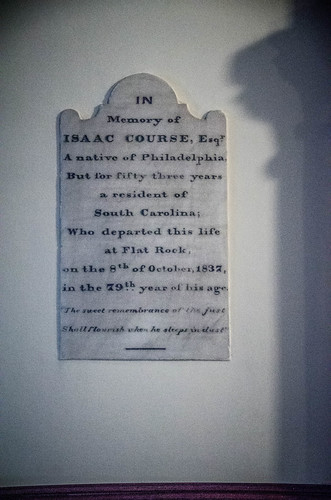

There were memorials on the walls, and even one in the floor.

There was an opening on the tower end of the building, and that led to a carpet staircase heading up into the tower. I just had to explore. It just went up one more level to a storage for choir robes. Oh well. I didn’t see any secret doors leading to subterranean chambers.

I thanked my hosts, made a small donation, and headed back to the car.

My next stop was about 20 miles up the road in Fletcher. I drove through the town of Hendersonville, then cut across country to Fletcher. There, on US 25, I found Calvary Episcopal Church.

Calvary Episcopal

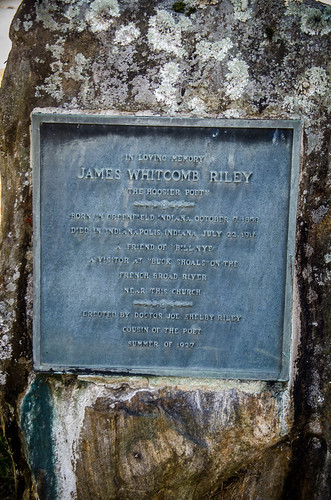

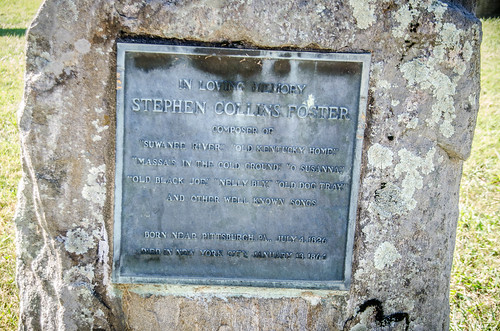

Even before I started my exploration of the church and its grounds I got distracted by an unusual feature. On the church grounds, but separate from the church buildings and cemetery stand two rows of monuments. These are rough granite monoliths with brass markers attached to them.

The individuals memorialized were completely random, as far as I could tell. Some had connections to the area, but others didn’t. The names included Jefferson Davis, Francis Scott Key, Stephen Foster, and “O Henry.” It looked like these were erected in 1928.

When I turned my attention to the church I began to wonder if I was in the right place. The building looked far to new to be from Jones’s era. I started to wonder if the Jones church was no longer extant, and this was a replacement.

The church was a Romanesque design, and I could see elements similar to the Church of the Holy Cross. So, the design looked like something Edward Jones would build, but something was still not quite right.

Another rough monolith with a brass marker said that the church had served as a barracks for Confederate soldiers, and it seemed to indicate that it was THIS church. That would make the age correct, but the bricks still looked too new.

It wasn’t until I got home and checked the church’s website that I learned the true story.

The original church building burned in 1935, with only the brick shell left standing. One stained glass window, the baptismal font, the Bishop’s Chair, and a few smaller items were saved. The congregation moved quickly to rebuild; Architect S. Grant Alexander, a Scotsman recently emigrated to Asheville, was engaged for the design.

The nave was lengthened and widened, but the west front of the old building, with its beautiful bell tower, were saved and incorporated in the new building.

Looking back at my photos I could see the difference between the new bricks and the old of the bell tower.

Oddly enough, Edward Jones’s name is never mentioned on the Calvary website. It says that the design was based on an original by 17th century builder Christopher Wren. Strange.

As for the cemetery, it’s still active. The cemetery is expansive, and felt peaceful. It looked like there were later generations of the families I found at St. John.

So far I had visited three locations attributed to Edward C. Jones, and I could definitely see similarities between these buildings and others designed by Jones. I was done with the North Carolina targets, but I had more to see back down in South Carolina. That’s going to have to wait until Part 3, though.