I’ve been wanting to have a “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off” for some time now with two of my great friends from Furman, Dwight Moffitt and Jami Sprankle. Since both live in Columbia the idea was that I’d ride down and we would see what all the city had to offer. While our day didn’t quite live up to the idealized movie standards, we still had a blast with a day full of insane asylums, hidden tunnels, harpsichords, safety coffins, and bagels. Oh Yeah!

The opportunity presented itself when Dwight forwarded me information about a tour of “Camp Asylum.” A group of archeologists from USC are excavating a Civil War prisoner of war encampment on the grounds of the old South Carolina State Mental Health Hospital on Bull Street. The site has been sold to developers, so the archeologists wanted to study as much about the site as they could before it was no longer available. Historic Columbia is offering tours of the dig on Fridays through the end of April. Jami starts a new job on Monday, so this Friday was the perfect time to explore.

Plans flew back and forth all week. We looked at the old Hidden Columbia videos on Facebook as well as other guidebooks and things to see what we might want to include in our Ferris Bueller Day. A cool soundtrack was a necessity. In the end, weather and family obligations limited our choices.

So, it wasn’t exactly like the movie. I drove down to Columbia in pouring rain. We didn’t swipe someone’s red convertible (although Laura’s was tempting), and it wouldn’t have made much sense in the rain. I picked up Jami in my rather sedate Subaru and then headed down to get Dwight.

The first stop was for bagels and coffee. As we sat the front caught up with us, and it started to pour rain in Columbia. We were still a bit early, so we drove past the Robert Mills house and the Hampton Preston house. It was still raining pretty hard as we toured the historic neighborhoods, and we were beginning to have doubts about our outing.

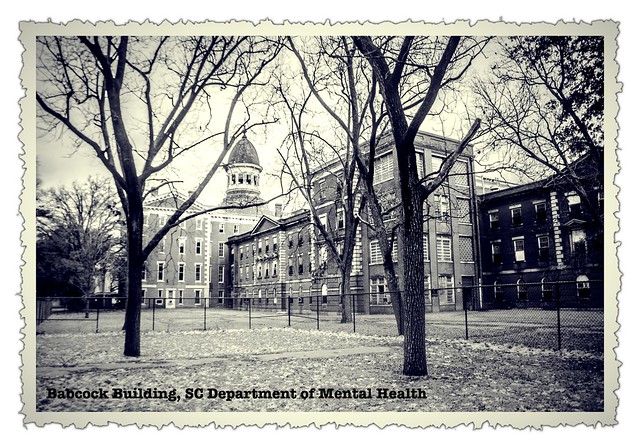

It was close enough to the appointed time that we drove through the gates of the Bull Street facility and onto the grounds. The historic Mills building was to our right, and the looming Babcock Building was straight ahead. A large sign with a camera and red circle indicated no photography, and I was starting to get worried. We had signed releases that said we couldn’t take photos of patients or employees, but it said nothing about the buildings themselves.

Our rendezvous for the tour was behind the Babcock Building. As we approached we could see areas covered with plastic to protect the dig from the rains. We pulled into a parking area nearby, and soon we were joined by other cars. Folks started getting out of cars and taking shelter, so we joined them. Even though the rain was beginning to abate, we wondered what kind of tour this was going to be.

It seemed a critical mass had gathered. Although he never introduced himself during the tour, Chester DePratter, the lead archeologist on the project from USC, began a lecture on the history of the location and on Camp Asylum.

According to DePratter, Union officers captured during the Civil War were used has human shields in advance of Sherman’s armies. One group of about 1500 officers were moved to several locations, including Macon, outside of Savannah, then to Charleston. In October of 1864 it was decided to move them to Columbia.

Unfortunately, nobody bothered to tell anyone in Columbia that they were coming. A train arrived with 1500 prisoners and no place to put them. A five-acre encampment was hastily created on the western banks of the Saluda River. There were no walls, but a “deadline” that was guarded by students from Camden Military Academy – basically kids with orders to shoot to kill any officer that approached the deadline.

Conditions in the camp were deplorable. Prisoners were forced to dig holes for shelter, which they covered with ragged blankets to keep out wind and weather. Food was scarce, and the prisoners were provided meager amounts of cornmeal and sorghum molasses. The camp became known as “Camp Sorghum.”

Despite the guards and river boundary, there were many escapes. In December of that year it was decided that the walled grounds of the South Carolina Lunatic Asylum, as it was then called, would be a better solution. The prison camp was moved across the river and to the grounds.

Conditions improved only marginally for the prisoners. Some were moved into wooden barracks, but the majority were forced to dig new pits covered with blankets for shelter. “Camp Asylum” was in operation only for a couple of months, from December 1864 until February 1865. In advance of Sherman’s march toward Columbia the prisoners were moved to Charlotte, then to Wilmington. Some say that the city of Columbia was burned because of the deplorable conditions at Camps Sorghum and Asylum.

Collection of Historic Columbia Foundation.

As for the dig…

The State Mental Hospital location has been in disuse since the 1990s when it was determined that clinical settings were better for mental patients than a monolithic hospital setting. The Babcock Building, large portions of the Mills Building, and most of the outlying buildings sat unused and deteriorating. This past summer the site was sold to developers. Realizing that time was short for any archeology on the site, DePratter proposed the dig to uncover information about Camp Asylum. The intent was to find evidence of the pits dug by the officers for shelter. DePratter and students from USC have until the end of April to complete their research.

By then end of this lecture, the rain had stopped, so we were able to walk out to some of the pits. We could see the layers of soil, including a layer of paving.

DePratter pointed out the two auxiliary buildings near the dig. We had been huddled under the porch for the Parker Building Annex. The Parker Building itself was constructed in 1897 to house African American patients in a segregated facility. It was demolished in 1980. Much of Camp Asylum and the subsequent dig are under the footprint of that building.

The annex was built in 1919 to house overflow from the main Parker Building. We were not allowed in, but there were several broken panes that let me sneak a couple of interior photos.

The other nearby building was the LaBorde Building, constructed in 1919 to research treatment of tuberculosis.

In front of the LaBorde building DePratter uncovered one of the pits to show the remains of a fire ring constructed from scavenged bricks. Charring was still visible from the camp fires of the prisoners. DePratter also said that they have uncovered the scarring of disk harrow plow blades, indicating that the prisoners had tried to grow some crops on the ground.

From there we moved to the actual location of the Parker Building. There were more pits, and DePratter pointed out the former locations of the wooden barracks housing some of the prisoners.

At this point the tour broke up, and we were allowed to wander the grounds with cameras. We were allowed to photograph the buildings from the outside, but were not allowed to enter. We were also not allowed to photograph any employees or patients, which makes sense. We first approached the fence surrounding the main Babcock Building and took a couple of photos.

The first was the Mills Building, named for architect Robert Mills. Constructed in 1828, it features the twin curved front steps typical of Mills’ designs, seen in the old Record Building in Greenville and his residence just a few blocks over in Columbia. Because that is still an active office building, we didn’t get any photos of it. (It was the one with the “No Cameras” sign out front.) Here’s a photo from the state website:

The Babcock Building was the second of the main buildings on the campus, and is much larger. It was constructed in four stages, from 1857 until 1875. As we walked along the back side of the building, Jami reminded us of a story I’d heard before. I don’t know if it is apocryphal, but supposedly some couple from out of state drove onto the Bull Street campus, looked up at the deteriorating dome/cupola on top, and declared it the “Ugliest State Capitol.” With all of the broken windows and deteriorating woodwork, it certainly is ugly at this point, with much need of renovation.

Behind the Babcock Building is the Laundry Building, built in the 1880s. In addition to laundry, it served as a mill, a carpentry shop, and an engine shop over time. On top of the building is a cupola that houses ventilation equipment.

Across from the laundry building was the old bakery, built sometime between 1889 and 1904. The building had some interesting brickwork, and there were a couple of missing panes that allowed interior views.

As we continued on around the Babcock Building, a security officer stopped us to make sure that we had the proper permits to be out on the grounds. All I had to do was hold up the paper and he was cool with it. They really don’t want anyone just out wandering around.

On the other side of Babcock we saw some interesting window casements, and also came across an old gurney under one of the covered walkways.

We continued on around the building to the front. We paused to admire the imposing facade, longing to go inside and explore further.

There were lots of other buildings on campus, and we didn’t know which were accessible and which were off limits. We kept to the Babcock Building, continuing our circuit. As we rounded the right side, we saw that lots more cars had arrived. Since the rain was now gone, students from USC were arriving to continue the excavations of Camp Asylum.

It was a great visit, but we really wanted to see more. I hope that some tours can be made available before redevelopment begins this summer. More importantly, I hope that the historically architecturally significant buildings can be preserved. DePratter said that some of them ultimately will be torn down.

For an excellent description of all of the buildings, this PDF file is great. It’s a 2009 zoning report submitted to Columbia City Council. I’ve also created a Google Doc with links to all of the resources I used for this post.

Wow!

Who do we need to talk to about doing a night time investigation there

I haven’t been down that way in a couple of years, but it’s my understanding that the property is now being redeveloped. You might contact the developers, but I doubt they would be willing to allow it, what with liability and all. I did find a link with more information about the new “Bull Street District” at this website. They have contact info listed on that site – info@bullstreetsc.com, 864-233-2580 x28 . Hope this helps!

I was watching a documentary on Bull Street Asylum and spotted a picture on the wall done by Robert Woods.

Is it for sale?

Bob was a family friend of mine and I loved his paintings.