Planning this trip I sent out two possible itineraries. One was to revisit the old Wesley Chapel ruins in Cherokee County and to try to located the old Union Grove Cemetery. Ultimately we decided on the Phoenix trek because it would make it easier for Dwight to drive up from Columbia to meet us.

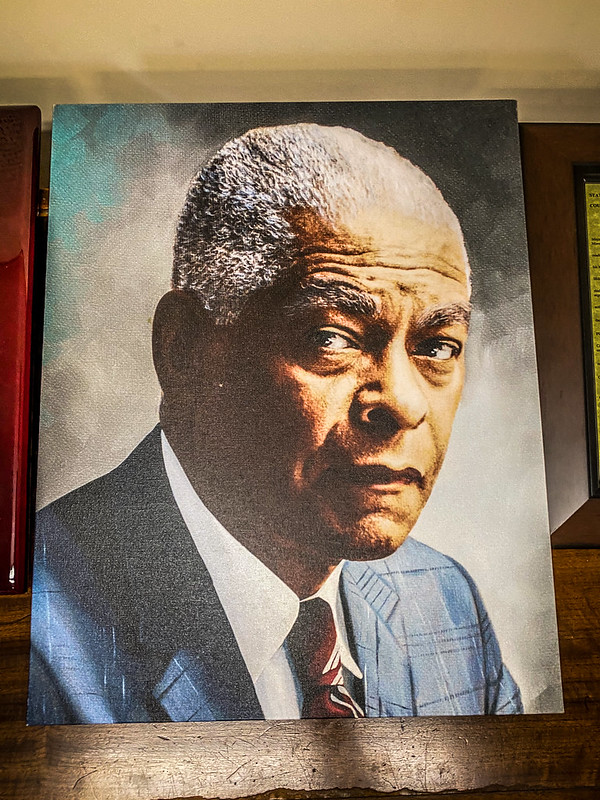

Our rendezvous point would be the Dr. Benjamin Mays Historic Site in Greenwood. Mays was a first-hand witness to the events in Phoenix in 1898 and was also a mentor to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. On this MLK Day it just seemed like an appropriate place to meet.

Houston and I picked up Alan, then drove down to Greenwood to meet Dwight. As soon as we got out of the car we were greeted by Rev. Chris Thomas, now director of the historic site.

Rev. Thomas asked if we were his 10:30 tour from Greenville. We were a bit taken aback. We said that we had driven down from Greenville, but didn’t know anything about a tour. When we described our quest for the day, Rev. Thomas invited us to join the tour. When Dwight arrived from Columbia we joined a couple from Simpsonville and started the tour.

Rev. Thomas is an excellent orator with an encyclopedic knowledge of the life of Benjamin Mays. The tour began in front of the house in which Mays was born and spent his early years. It was moved to this site from its original location near the community of Epworth in 2004 after being neglected by its owners. In this house in 1894 Mays was born to Hezekiah and Louvenia Mays, former slaves. Epworth isn’t far from Phoenix, so that chaos of the election riot spilled over into Mays’ community. Mays relates the following memory in his biography:

“I remember a crowd of white men who rode up on horseback with rifles on their shoulders. I was with my father when they rode up, and I remember starting to cry. They cursed my father, drew their guns and made him salute, made him take off his hat and bow down to them several times. Then they rode away. I was not yet five years old, but I have never forgotten them.” ….”That mob is my earliest memory.”

“After the Phoenix Riot, never a year passed in my county that there were not several brutal incidents involving Negroes and whites. In the months following the Phoenix Riot, I had seen bloodhounds on our land with a mob looking for a Negro,” Mays recalled. “I saw a Negro hiding in the swamps for fear of being caught and lynched. Negroes got the worst of it. Guilt and innocence were meaningless words: the Negro was always blamed, always punished.”

Benjamin Elijah Mays, Born to Rebel: An Autobiography, 1971

Rev. Thomas gave us more information about the early life of Mays, then invited us into the house.

The exterior of the house looked a bit different from my 2020 visit. There were new boards and lots of construction as some of the worn boards were being replaced. Here are a few photos from that 2020 visit.

The interior of the house was unchanged from what I remembered. The house was furnished with period items donated by local patrons. Some of these were authentic to the Mays abode, but most were just from the same time.

Houston and I are distantly related to William Jennings Bryan Dorn, a Congressman from Greenwood who opposed desegregation. Because of Dorn’s views, we weren’t especially proud of that connection. Rev. Thomas gave us reason to rethink that view. In his later years, Dorn became a supporter of Mays and even worked to make the Mays Historic Site possible. On the wall of the small house was an affidavit signed by Dorn confirming that this was Mays home.

It wasn’t the last time this day that we would have to rethink our views. As Rev. Thomas kept pointing out, the true history of civil rights isn’t quite so black and white, pun intended. It’s much more complicated.

Behind the small house the garden where I met Loy tending corn was now planted in cotton. The Mays family were renters rather than sharecroppers, so they realized more income from their crops. As with farms across the south, cotton was one of their most important crops.

From the Mays house we walked over to the Burns Springs School on the site. This isn’t the school that Mays attended, but it’s an example of the type of school he might have attended. Here are two exterior shots I took in 2020.

The interior is just a single room with a small stove.

Rev. Thomas took the opportunity to tell us about this specific school as well as Benjamin Mays’ education.

After Mays time in the one-room school he continued his education at a boarding high school sponsored by South Carolina State, much to the dismay of his father. (I guess he was “dis-Mayed?). Mays then went to Bates College in Lewiston Maine, then completed his masters and doctorate at the University of Chicago.

The most modern building on the historic site houses artifacts from Benjamin Mays career as a minister, teacher, and advocate for civil rights. Mayes taught at Howard University, and in 1940 was named president of Morehouse College in Atlanta. It was during his Morehouse years that Mays taught a young Martin Luther King, Jr. He also met with Ghandi and even consulted with Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. After his tenure with Morehouse College, Mays continued to promote civil rights, working with Jimmy Carter. Benjamin Mays died in 1984.

One last story that Rev. Thomas told us was about Mays relationship with Margaret Mitchell, the author of Gone with the Wind. Mitchell’s work was considered insensitive and racist, so she was not held in high regard by many in the Civil Rights Movement. After her death it was discovered that Mitchell had been a regular donor to Morehouse and had paid for many deserving African American students to attend college and specifically medical school.

We thanked Rev. Thomas for letting us join his tour and for sharing his knowledge of Dr. Benjamin Mays. Now, though, it was time for us to continue our MLK Day ramble.

Continued on the next page…