Last time I gave a brief introduction to the camera obscura, describing what it was and a tiny bit of the historical background. This time I’m going to cover my personal experience with these systems.

I started playing with cameras when I was about 9 years old. My first was a hand-me-down Brownie Box camera that I got from my sister, Glynda. Unfortunately, none of the photos I took from that era survive, but I still have that camera. That old camera wasn’t much different from a pinhole camera – just a basic light-tight box with an aperture and some sort of capture medium (ie, film.) As a teen I spent one summer making actual pinhole cameras with my brother, Houston. We experimented with various styles made from oatmeal boxes and brass shimming with different aperture pinholes. Again, none of those images survive.

While my father was principal of Gray Court Owings School, my brothers and I had the run of the place. We found an old unused closed that had been used as a changing room for basketball teams long, long ago. The room was under the stage, and had running water. It was the perfect place to commandeer for a dark room, so that’s where we set up our chemicals and enlarger. Stephen and Houston did more of actual dark room work, but I remembered that location, hidden away under the stage of the old auditorium under a trap door.

There was a long lull while music, college, rock climbing, and river running (somewhat in that order) took precedence over photography. 16 years after building my first pinhole camera, I found myself teaching a unit on light to class of gifted 7th graders at GCO, and I figured the best way to convey some of the concepts was through photography.

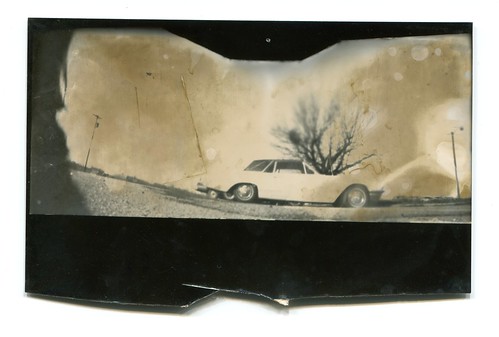

I remembered that old dark room from long ago. It was still hidden, and no one was using it. Once again I commandeered the room for a the same purpose. I had my students build various pinhole cameras, and we got some interesting shots. Here’s the only one I could find. This is actually a scan of a contact print made on a scrap piece of photographic paper. We weren’t sure if the process would even work, so we didn’t want to waste a whole, good piece of paper.

At that point I still had not heard the term “camera obscura” (even though I had been using a “dark room” for many years.) In 1987 I was in Edinburgh, Scotland, and we came across the famous camera obscura at Edinburgh Castle on the Holy Mile.

This location was typical of tourist cameras obscura of that era. A lens was mounted high in the tower and an image of the surrounding countryside was reflected down to a table by means of a prism. Visitors would stand around the table and view the activity outside. In an age not dominated by digital cameras and video everywhere, this was quite the phenomenon.

Unfortunately, I was traveling on a wafer-thin budget, and spending one more pound to see this thing didn’t seem like a good idea. When I got home and found out what I had missed, though, I mentally kicked myself. At that point I learned more about cameras obscura, and decided to work those into my 7th grade photography studies.

In 1990 we invited a guest artist (whose name I can’t remember) to visit our classes. This guy built large cameras obscura, and brought several with him. Here are several shots of me assisting him in constructing a camera obscura, and our classes taking turns visiting.

Students would go inside and the guy would stand on his head and do other crazy things to be projected on the interior walls.

Our class built our own camera obscura from a refrigerator box. We sealed it up with black tape, put an aperture in one side, and a sealable flap for a door in the other side. A photo of it ran in the local Laurens Advertiser, but I haven’t been able to find a copy of that photo. We even tried using it as a huge pinhole camera, with mixed results.

Fast forward another 16 years or so to 2006. Laura and I returned to Great Britain, and this time we were visiting the Royal Observatory in Greenwich.

The Royal Observatory Camera Obscura is in the small building to the right in the above image from the Greenwich website, and features a domed building with pinhole at the top. The pinhole can rotate, presenting a 360 degree image from the top of the hill. The image is projected onto a table.

I wasn’t able to get any good images from the inside of the camera obscura. I didn’t have a tripod and it was just too dark. Still, it was a fascinating experience.

Since that 2006 trip I’ve only delved into pinhole imagery once. I turned my Nikon D50 DSLR into a pinhole camera until I realized that I was getting crud on my image sensor. I got some interesting images, though.

Because of the potential for damage to my image sensor, and because it’s a pain to set up all the chemicals and a dark room for traditional pinhole photography, I think I’m going to shy away from that for awhile (unless someone has a dark room they are willing to let me use.) Still, those same concepts can be explored using a camera obscura. I’m hoping to put one together on a small scale and see what images I can capture from it. We’ll see.

Loved this personal history! If you are interested in camera obscuras, you may want to check out the pre-photographic workshop at the George Eastman House this summer. Participants build their own small camera obscuras, and use larger ones. They also use a camera lucida to make drawings, and a physionotrace to make silhouettes. http://www.eastmanhouse.org/events/detail/photo-workshop-12-2012

Regardless, I hope you can figure out some practical way to use camera obscuras or pinhole photography- seems like a fun project!