Laura and I were working on her mother’s estate and had an appointment in town with an insurance agent. We arrived a bit early, so Laura suggested that we try to find the old Northern State Hospital just outside of Sedro-Woolley. It had been featured Ghost Hunters, one of Laura’s favorite shows, so she wanted to see it. When we arrived we found only open space and ruins. We had to get back for our appointment, but I had seen enough to know that it warranted another visit. So the next morning I paid a visit to the old mental asylum.

As usual, first a bit of history…

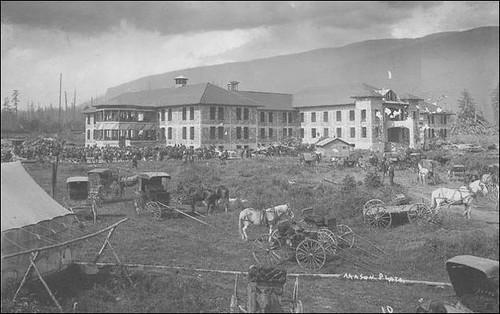

Northern State Hospital opened in 1912 as the “Northern Hospital for the Insane.” It was the third of Washington’s mental institutions. 800 acres of land at the foot of the Cascades in the Skagit Valley were cleared and the campus was landscaped. This photo from the Washington State Archives shows opening day for the hospital on March 25, 1912.

The original buildings were of Spanish colonial design. This motif was carried out through other subsequent buildings on campus.

As with many mental institutions of the period, treatment of mental illness was often experimental and somewhat barbaric by today’s standards. The notion of what even constituted mental illness was often misunderstood and many were admitted simply because they were problems in society’s strict settings. According to a Seattle Times article from this past April…

The word was defined broadly. Patients at Northern State, which housed as many as 2,700 souls in the early 1950s, ranged from the violent mentally ill (a small minority) to the mildly disturbed — and beyond, to epileptics, alcoholics, drug addicts or mere social nonconformists. Many were immigrants.

Treatments were consistent with the times, and many are now considered barbaric. Doctors and nurses administered regular electric-shock treatments to many patients, including women incarcerated for “menopausal depression.” Heavy sedation, sometimes with experimental drugs, was common. “Insulin coma therapy” was employed, and some patients, beginning in the 1940s, received a new wonder cure, the transorbital lobotomy.

The article goes on to say that even with these treatments, “Northern State established a reputation as one of the country’s ‘good’ mental institutions — one operated with more compassion and care, it was argued, than the state’s other two regional facilities.” According to the Skagit River Journal…

Visitors noted how much more modern Northern State was than the other two state hospitals. They remarked that the buildings were well ventilated and lit and that the newer wards had their own recreational halls and dining rooms. Also of note were the library and a recreational program that included movies, dances, concerts and baseball games. [Dr. Charles H.] Jones [director of the institution in the 1950s] explained that there were 650 new patients per year on average, 400-plus were discharged and roughly 200 died or were transferred.

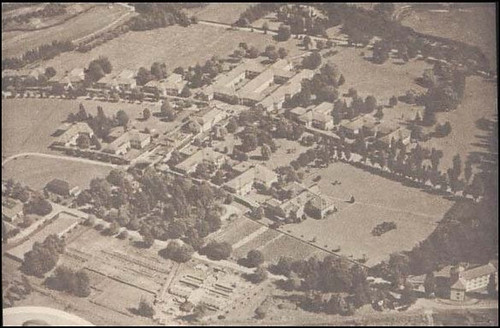

Even so, the facility became known as the “Bughouse”, not necessarily as a pejorative, but in reference to the town of Sedro’s former name, “Bug.” The campus grew to include 1,100 acres, including pasture land for farming, a dairy and several support buildings along Hansen Creek.

Inmates were given jobs on the farm to help with their treatment and to help support and provide food for the facility. The Skagit River Journal goes on to describe the extent of the farm…

The poultry farm was also sizable, supplying 36,798 pounds of dressed hens and fryers. Jones was determined that enough eggs be produced to allow at least one per patient per day. To that end, 139,207 eggs were laid that year. The pig farm produced 258,737 pounds of dressed pork and 23,779 of cured hams. Crops were also plentiful: fresh fruit, 185,068 pounds; berries, 61,046; potatoes 1.1 million; kitchen vegetables, 1.1 million. The farm also produced 324 tons of hay for the animals as well as 345 tons of silage in a new pit silo. A summer cannery processed the fruits and vegetables from the hospital farms as well as those from donated produce from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

According to the Seattle Times article…

Occupational therapy was Northern State’s mantra, and many patients worked on the dairy farm. An offshoot canning operation produced large quantities of canned meat, applesauce and other goods. Manure spread from the dairy on local fields produced spectacular spring wildflower displays. Herds of deer and elk strolled around the campus, as they do today. Self-contained Northern State had its own weekly newspaper, and even a competitive baseball team.

By the time Northern State closed as a mental institution in 1976 tens of thousands of patients had passed through its doors. Many had died while confined there. The hospital had its own cemetery at the western edge of the campus. This, along with the deterioration of the buildings after its closure, gained Northern State the reputation as a haunted area.

As I mentioned in the opening, it was this haunted reputation through which Laura and I first became aware of Northern State Hospital several years ago. In the season 3, episode 13 of Ghost Hunters the crew visited Sedro-Woolley and Seattle. It was fun watching them come through town and show landmarks with which we were familiar.

Sadly, that show just heightened the location’s reputation, and the facility has had to put up with trespassing and other intrusions from would-be ghost investigators. I found several YouTube videos from these groups, but won’t post them here.

Back to the present day…

Laura was our navigator for our first excursion. She had searched for “Northern State” on the Google Maps app on her phone and it led us to a park with wide open fields and the deteriorating barns. We began to wonder if the hospital itself had been demolished and the park had replaced it. We didn’t have time to explore further because of our appointment. However, when I checked Google Earth at home I found that the hospital was, in fact, intact. Laura’s search had taken us to the park, but the main buildings and campus were to the west of our visit.

Tuesday was still supposed to be sunny, but with clouds rolling in by mid-day. I decided to get an early start. It was cold and frosty and clouds had already started gathering. Mount Baker’s peak was obscured by lenticular clouds.

I wasn’t sure what I’d find, but I wanted to see if I could catch a glimpse of the main campus. I held out no hopes of being able to visit and see the interior. Instead of turning onto Helmic Road from Highway 20 as we had the day before, I turned onto Fruitdale Road. This led to an access road with signs proclaiming a “closed campus” and “No Trespassing.” There was a guard station, but it didn’t looked occupied. There wasn’t a gate as far as I could see. What buildings I could glimpse looked like the place was still occupied and in use. I decided not to barge on in, but to start with the park.

Actually, I started with the cemetery. A small fenced area with parking spaces had a sign identifying the area. Another brick structure held a small memorial plaque.

The cemetery looked like it was just an open field. I could see only one monument through at the back of the property. I made a bee-line for it, stepping through hoar-frost and ice needles.

As I walked across the field I began to notice slight square indentations. Some of these held markers with a number and initials.

The one small monument was for a John Davis. Other square markers lined the property along the back. There was nothing to indicate why Davis would merit a larger marker.

The April article from the Seattle Times describes the problems with the cemetery and why there are so few markers visible.

Thousands of people died while confined here. Unless a family member claimed the body, its disposal was up to the state. Most patients known to be of Protestant faith were cremated, in an on-campus crematorium that operated from the 1920s until the early 1950s, when a funeral home took over burials. Years after the furnace was shut down, hundreds of cremated remains were found stored in tin food cans bearing patient numbers. They eventually were laid to rest in a mass grave at a Mount Vernon cemetery.

Earlier patients were buried in Northern State’s own cemetery, a 1.5-acre plot on the far east side of the grounds. The grassy field is notoriously swampy and covered by a thick thatch. Burial in the soupy soil was difficult — stones reportedly were placed in some makeshift coffins to keep them from floating up before they could be covered.

On the surface, the opposite problem: The “grave markers” — brick-sized blocks — repeatedly have sunken into the thatch, literally disappearing.

Identifying those buried in the cemetery is a challenge. Records have been lost, and in some cases have been non-existent. The Seattle-Times article goes on to say, “Even in death, the stigma of mental illness haunts these departed souls. The lack of names is a clumsy result of privacy laws that protected family surnames from being associated with an asylum.”

The brick wall with the engraved plaque was a senior project by a group of Sedro-Woolley High School Students. There was also an attempt to locate and identify some of the graves. A community-based group is also attempting to identify those buried therein, as well as maintain the cemetery. Find-a-Grave has 385 names listed on their site for the cemetery, but there are no photographs. Or, rather, the number of photographs is consistent with the number of markers uncovered and identified.

It felt a bit odd. Apart from visiting Laura’s parents’ graves, I haven’t explored any cemeteries while here in Washington. I was only here as a starting point for my exploration of the larger park and Northern State Hospital complex. It was time to continue those explorations. That comes in Part 2 of this series.