The story of a “Crybaby Bridge” seems to be a common trope in tales of the paranormal. There are Crybaby Bridges all over the country. Each bridge has a similar story. Usually, a distraught mother kills a baby by tossing it into the water below. Thereafter, any travelers crossing the bridge at night will hear the cries of the unfortunate child.

South Carolina has no less than three Crybaby Bridges. There is the one with which I’m most familiar, a steel trestle bridge over the Tyger River in Union County. This is in the Sardis Community near Rose Hill Plantation. This is still an active roadway and I’ve crossed that bridge many times, though I’ve never heard the eponymous cries. I’ve even launched kayak trips down the Tyger from this location.

The second bridge is in Pageland, SC. I don’t have any photos, but it appears to be a much smaller bridge with a somewhat convoluted story. The creek is known as Crybaby Creek.

Crybaby Bridge over High Shoals on the Rocky River in Anderson County seems to be the most well-known such bridge in South Carolina. After exploring Underground Anderson with Alan Russell we decided to visit this haunted spot.

The old steel trestle bridge was replaced with a new concrete bridge in 1987. We parked along the road and looked at the old bridge from the new one.

From the other side of the modern bridge I got a couple of shots of the Rocky River and High Shoals.

As we took the photos I jokingly wondered how these hauntings work. When the old bridge is finally gone, do the cries transfer to the new bridge? On a related note, do you have to be standing on the old bridge in order to hear the cries?

Was this steel trestle bridge even the origin of the story, or was there an even earlier bridge? That last question made me wonder about the history of this area in general. As it turns out, the High Shoals area has a long history that predates both the town and county of Anderson.

Even before European settlers came to the area, this spot had a reason to be haunted. According to historian Frank Dickson in his book Journeys into the Past: The Anderson Region’s Heritage, “The Indians maintained a burial place at High Shoals, six miles south of Anderson, and also had one on the land of Mrs. Henry McFall near High Shoals.” An Indian burial ground nearby? That would seem to be a surefire way to find a haunting even without a crybaby.

In the late 1700s through the early 1800s High Shoals fell just east of the main road from Pendleton to Abbeville. This was known as the “General’s Road” because it was the route General Andrew Pickens preferred while traveling between the two settlements. Robert Mills’s 1825 map of the Pendleton District shows “Widow Pickens’ Mill” at High Shoals, though there is no indication of who the deceased husband might be and that individual’s relationship to Andrew Pickens. The shoals also bore Pickens’ name when the map was made.

The crossroads of High Shoals Road and the General’s Road became a stopover for weary travelers. “Varennes” was the name of a local school,, church and tavern. According historian Louise Vandiver in her History of Anderson County, the area was named by French Huguenots who had settled to the south in Abbeville. It came from the French word for “wasteland.”

The township lying south of Anderson was named from old Varennes church. It had been a sort of social center for many years, having been one of the earliest churches and schools in the section.

The word Varennes is French and means waste land. How the school, for it preceded the church, came to be called by so unpromising a name can only be conjectured. French Huguenots settled Abbeville county and town, and named it from their old home in France. It is probably that this section lying north of the little town was at first inhabited by Indians, and came to be known to the white people as the wast land — Varennes. When the tongue became Anglicized, the meaning of the word was lost, but it was a pretty word, sounded well and so came to be given to the school and church, and also to a sort of trading post which grew up there; then when a township was to be named, why there was the pretty name ready to be be bestowed upon it.

Louise Vandiver, History of Anderson County, 1928

The school is indicated as “Academy” on the Mills Map. Also shown on the map is Varennes Tavern and PO, most likely the trading post of which Vandiver wrote. Carolana.com indicates that this post office came into being around 1810. In 1866 it moved to a new location, but Varennes wasn’t closed as a post office until 1901.

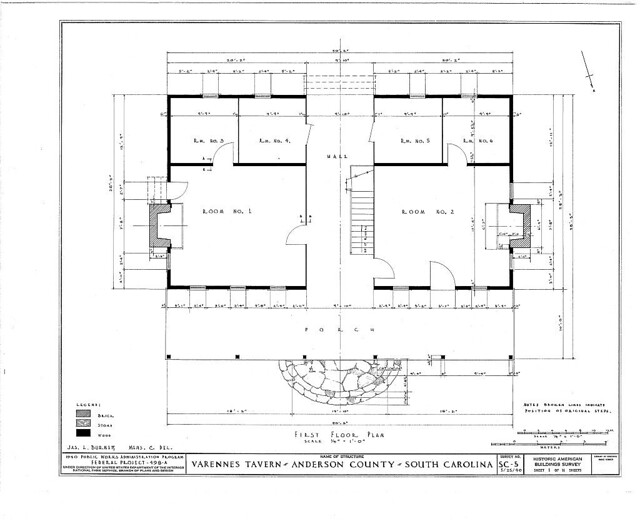

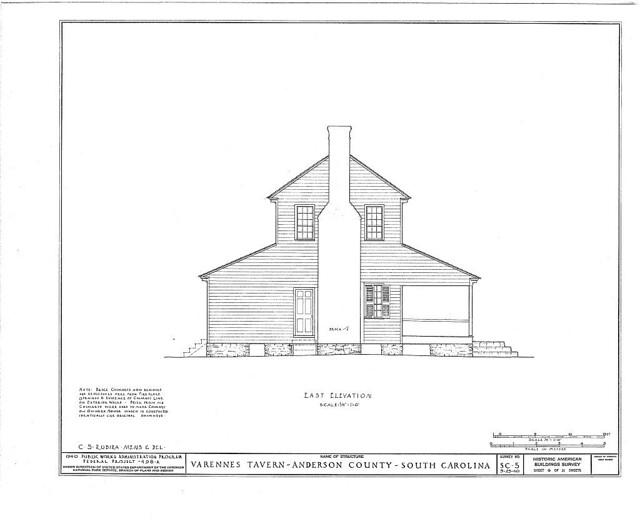

Varennes Tavern sat just south of the intersection of High Shoals Road and present-day Highway 28. Sadly, the tavern burned sometime in the 1980s, but the Library of Congress has not only photos of the tavern, but floor plans and drawings of architectural details on its website. There were taken sometime in the 1940s.

High Shoals became a favored spot for picnics. In historic newspapers I found several mentions of the location as different groups held events there. I also found an old postcard that shows a group lounging on the rocks.

Falling water means power. The Mills map shows a mill in this location. In the mid 1800s the mill was owned by William Brissey, who also capitalized on the popularity of the location. In the book Anderson County Sketches, Elizabeth Belser Fuller describes the Brissey operation…

Early in this century one of the most popular recreation spots in the vicinity of Anderson was High Shoals on the Rocky River. The old water mill, then in operation, was a big attraction; and out in the river the huge rocks were big enough to hold a picnic party. About 1920 the mill was operating six days a week and the owner, the late W. L. Brissey, made something of a showplace of the area, adding a small zoo and pavilion.

Walter McKinney made a sketch of the old mill in 1947. This sketch was included in the book.

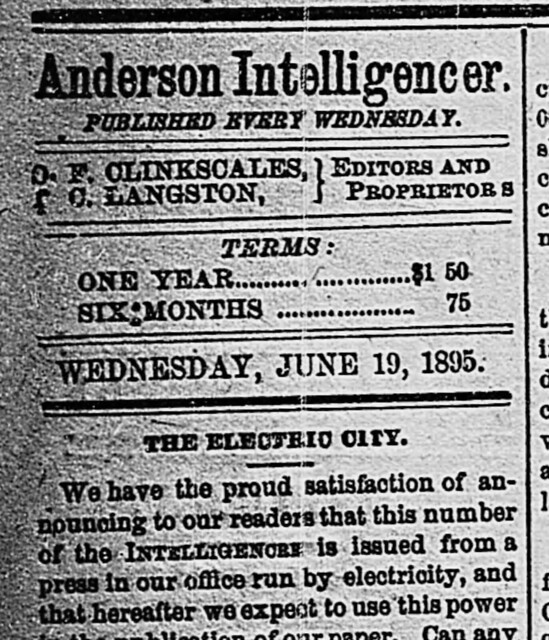

Young engineer William Whitner also recognized the power of the water at High Shoals, but he wanted to convert it into a different type of power. In 1894 Whitner built an electric generating power plant at the shoals.

Whitner conceived the idea of generating alternating current electricity using turbulent river water. For advice he went to New York to see Nicholas Tesla, the great Serbian scientist who had perfected the alternating current motor. A turf war was in progress between Thomas Edison, an advocate of direct current, and Tesla, an alternating current advocate….

…Whitner returned to Anderson in 1894 and leased a plant, in McFall’s grist and flour mill at High Shoals on the Rocky River 6 miles east of town, for his newly formed Anderson Water, Light & Power Company. There he installed an experimental 5,000 volt alternating current generator to attempt to generate and transmit electric power to the water system pumps at Anderson’s Tribble Street power and water yard.

It worked, and ended up supplying enough power to light the city and also to operate several small industries in Anderson. The Charleston News and Courier promptly dubbed Anderson “The Electric City.”

Dave Tabler – Appalachian History

Electricity was transmitted to Otis Boyd’s textile mile six miles away via power line. It was the first time power had been transmitted at a distance in the South, and it earned Anderson its nickname “Electric City.” However, the High Shoals plant proved inadequate to meet the demand for electricity, so in 1897 Whitner built a new generating plant on the Seneca River at Portman Shoals.

But what about that Crybaby Bridge?

There had been a series of wooden bridges across the Rocky River. The Mills 1825 map shows a crossing here, but it’s unclear as to whether or not this is a bridge or a ford. I couldn’t find information about those earlier bridges, but I did find an article in a 1931 edition of the Greenville News saying that a new 192 foot bridge would be built across the river.

This bridge lasted about 20 years, into the 1950s. Apparently it didn’t hold up very well and vehicles started falling through the deteriorating wooden platform. In 1953 there was a call for a for a new bridge, also reported in the Greenville News.

A new bridge was built across the river…sort of. A new platform and supports were constructed, but the trestle portion came from another bridge.

On Highway 17 south of Charleston there was a long steel trestle bridge across the Edisto River. This was a triple span bridge built in 1919 by the Virginia Bridge Works with a swing trestle in the middle to allow for river traffic. In 1952 the US 17 bridge was replace. The steel superstructure was removed and reused in other bridges. One of those spans made its way to Anderson County to become the new High Shoals Bridge.

This image is from a fantastic 1981 survey entitled Metal Truss Highway Bridge Inventory for the South Carolina Department of Highways and Transportation by the late Dr. Richard Elling.

In 1987 the new concrete bridge was built, replacing this bridge.

If the legend of the crybaby is specific to the metal truss bridge, then the supposed tragedy must have occurred between 1953 and 1987. The Historic Bridges website describes the tragedy this way.

On this particular bridge, the sounds of a crying baby, sounds of a mother searching for her baby, or a ghost of the mother approaching visitors to see if they had her baby were supposedly possible events that could occur here. The legend apparently began with a story of a mother who jumped off the bridge with an illegitimate baby to commit suicide. These legends and stories and their truth or untruth have no bearing on the historic significance of the bridge but they do shed light on the local stories and value that can accumulate in a local community on old/historic bridges, even technologically insignificant old bridges.

As for truth or untruth, I figured that something this tragic would be reported in local news. I couldn’t find anything about a suicide, or any other fatal tragedy for that matter. There was nothing in any of historical newspaper archives. I’ve found no verification that the events actually happened.

That doesn’t surprise me. Crybaby bridges are urban legend. According to The Occult Museum website, the first supposed Crybaby Bridge was in Maryland. From what I’ve read, it seems that these stories arose in the 1960s. The stories reference events from the Civil War through the 1960s, but there seems to be little documentation for these events. The Pageland Crybaby Bridge tragedy supposedly took place in the 1940s.

In 1999 an early Internet hoax spread the idea that LOTS of bridges across the US had Crybaby stories attached to them, giving rise to the term “fakelore.” Many of the stories had similar elements and some of these fake legends have wound up on listicles and click bait articles about “Most Haunted Bridges.”

Even so, there is something compelling about stories of haunted bridges, as evidenced by the widespread Crybaby Bridge stories. Even the stories of trolls under bridges are a testament to the mystique of crossing a body of water.

Poinsett Bridge in Northern Greenville County is supposedly haunted, as is the “Booger Jim” bridge in Cherokee County, the Ghost Creek Bridge in Laurens, and the Gervaise Street Bridge in Columbia. The older the bridge, the better.

Crossing water always presents hazards. There are true stories, such as the tragic Harper Ferry’s drownings in 1920. Water crossing also tend to be the most historic places and the first places to provide water, power, and a place of employment for settlers. It’s no wonder that tales of paranormal spring up around these locations.

Finally, the Crybaby Bridge in Union and the High Shoals Bridge share a unique heritage. The Sardis/Gist Bridge over the Tyger River in Union County, light High Shoals, is a relocated bridge. It was also on US 17 over the Sampit River near Georgetown. The metal superstructure was moved to Union in 1961.

So, the next time you’re crossing a remote bridge late at night, pause for a bit. Who knows what you might see and hear.

Tom, thanks for continuing to share your adventures and the hidden history! I so enjoy your interpretation of events and places!