I can’t believe I haven’t posted anything here since Halloween. November was a blur, and December was upon us before I knew it. We have now entered the most chaotic time for professional musicians. This past week alone I’ve had either a rehearsal, a performance, or a group jam session every day.

Since stores have been playing Christmas music for the entire time between posts, perhaps this is a fitting segue into this season. I thought I’d repost a story from 2010 about one of my favorite musical resources, the Oxford Book of Carols…

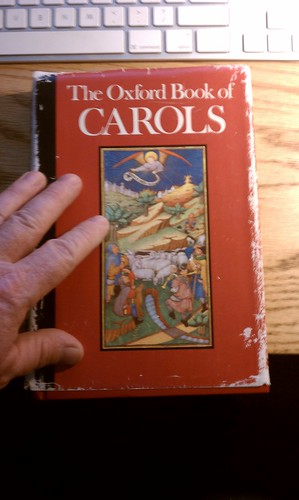

Nope, no ghosts this time (that I know of, although I did watch Scrooged this evening.) No, I’ve been spending some time with an old friend – my well-worn copy of The Oxford Book of Carols.

The Oxford Book of Carols was originally published in 1924, and edited by Percey Dearmer, Martin Shaw, and Ralph Vaughn Williams. It was supposed to be the definitive collection of Christmas Carols. It’s still widely available, as is the New Oxford Book of Carols.

As a young choir director I would check a copy of the book out of the library each year as a reference, and to give me ideas for upcoming Christmas programming. One Christmas my mother-in-law gave me my own copy. Understand that this was in pre-Internet days. You couldn’t just log onto Amazon.com and find a copy. Her neighbor was a retired reference librarian, and was able to track down a copy for me.

So, quick – name your favorite Christmas Carols. You would probably come up with something like this…

Joy to the World O Come All Ye Faithful Hark! The Herald Angels Sing Silent Night Angels We Have Heard on High Away in a Manger

You might be surprised to find that none of those beloved carols are in there. Some of those titles don’t even fit the narrow definition of “Carol” applied to the songs that are in the collection. To be a supposedly definitive work, there is much that is lacking, as well as some surprising inclusions.

The preface to the Oxford Book of Carols contains an interesting history of the Christmas carol, but the language gives some clues as to why certain pieces were omitted. Terms such as “doggerel” are used to describe some carols, and it even says that “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing” is a “composition of no merit.” Those are strong opinions.

Even with all its faults omissions, though, there is some fascinating content. Carols aren’t limited to Christmastide. There are entries for Easter carols, Advent carols, and pretty much any other religious festival of the year. Some, such as “Tomorrow Shall Be My Dancing Day” begin with Christmas, but subsequent verses cover the entire life of Christ.

According to the Oxford Book of Carols, the term “carol” came from a French root meaning “to dance”, so a song about a Dancing Day seems appropriate. Many of the songs have a lilting quality which would lend itself to dance, and there are many references to joy and making merry. For example, note where the comma is placed in the title “God Rest Ye Merry, Gentleman.” The carol isn’t talking about Merry Gentlemen. I guess a good literal translation would be “Relax, Dudes.”

As for the dancing aspect, that association resulted in many of these carols being banned from the church. It wasn’t until the 1800’s that many of these came back into use in church services. Perhaps it is that lack of a “caroling” nature that led to the omission of so many well-known Christmas hymns.

Many of the carols in the book couldn’t be considered hymns at all, and are only tangentially Christian. These focus more on the partying aspects of the holiday with only a brief reference to the religious aspects. Various wassail songs and The Boar’s Head Carol comes to mind…

The boar’s head in hand bear I Bedecked with bay and Rosemary; I pray you, my masters, be merry, Quot estis in convivio!Caput apri defero, Redens laudes Domino!

The Boar’s Head Carol is also a classic example of a macaronic carol (and, yes, that is the same base word from which we get macaroni.)Macaroni originally referred to peasantry, and eventually narrowed its meaning to the rough pasta that the peasants in Italy ate. However, at one time it also referred to just about anything related to peasantry.

A macaronic carol intersperses common language with Latin. These were usually snippets and refrains from the Latin service texts. Another example is In Dulci Jubilo:

In dulci jubilo Now sing with hearts aglow! Our delight and pleasure Lies in praesepio, Like sunshine is our treasure Matris in gremio.Alpha es et O!, Alpha es et O! (alpha and omega)

Most modern hymnals now have this as “Good Christian Men, Rejoice” or “Good Christian Friends, Rejoice.”

There are many carols in the collection that use allegories and allusions, some of which may lack context in a modern setting. There are lots of Biblical images, and allusions to purity, such as references to either Mary or Jesus as a Rose. “The Holly and the Ivy” is fairly well-known, and the allusions are described within the carol text itself. However, “Jesus Christ, the Apple Tree” and “I Saw Three Ships Come Sailing In” may be harder to comprehend. The title of “The Carnal and the Crane” itself is perplexing. The actual carol describes a theological discussion between two wading birds. Weird.

I’m also fascinated with the carols that bear the names of English towns or provinces. These include the Coverdale Carol, Gloucester Wassail, Hereford Carol, Somerset Carol, Somerset Wassail, Sussex Carol, Sussex Wassail, Wexford Carol, and Coventry Carol. These were usually towns associated with the origins of these particular carols. Some of these have a fascinating history, though.

Take for example, the Coventry Carol. First, though, let’s back up a couple of hundred years. During the middle ages, especially with liturgy that involved some dramatic event, some priests had begun reading the Latin text with a bit more drama. Some had even resorted to bringing in props for illustration, such as manger, or congregants to represent characters within the story. The pope banned these from the church, but they were so popular that the townspeople took them up outside of the church context, and created what was known as the “Mystery Play.”

In the towns, the most organized groups were the trade guilds, and these were the groups that often took on the mantle of putting on the mystery plays. The plays were often staged on moveable carts known as “pageants,” giving us the origin of that term.

In the town of Coventry, the Pageant of the Shearmen and Tailors was a popular part of that town’s mystery play, and described the Massacre of the Innocents by King Herod. The Coventry Carol provided the musical context for the pageant.

Lully, lulla, thou little tiny child, By by, lully lulay. O sisters too, How may we do For to preserve this day This poor youngling, For whom we do sing, By by, lully lulay? Herod the king, in his raging, Charged he hath this day His men of might in his own sight All young children to slay.

The Christmas Pageant is still an integral part of many modern churches. I remember putting on a bath robe and fake beard several times in my childhood to portray either a shepherd or wise man. (Although we never sang the Coventry Carol, to my knowledge.)

The Oxford Book of Carols is nearly 90 years old, and its focus tends to be on the more ancient carols. So where does that leave us today? There are some excellent Christmas songs that I think would fall into the carol category, such as Alfred Burt’s carols. There are two songs I’ve never cared much for, but they actually have much in common with the songs from the OBC. “The Little Drummer Boy” is allegorical and similar to many of the early mystery plays. I never could stand the song “Do You Hear What I Hear?” but its imagery and conversational style aren’t much different from “The Carnal and the Crane.” I’m sure, though, that the OBC editors would have dismissed these as “compositions of no merit.”

Carols and their history do fascinate me, and I like listening to all sorts of arrangements. The Festival of Lessons and Carols is my absolute favorite church service, and I enjoyed conducting these services myself as a choir director.

As for the Oxford Book of Carols, I always find it to be an excellent reference book. However, I never found it to be a good source of material for my church choirs. It did help me understand the music a bit better, but the narrow strictures of what constituted a “carol” often left me with with little I could use. Still, I like pulling it out and perusing the old texts. It would be interesting to see what would be included in the next OBC, several hundred years from now. Perhaps “Do You Hear What I Hear?” will make the cut.

Tom, John Plunkett shared some links to early-carol history that may be of interest… Audio: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jos2XjOlYVY and lecture-text

https://www.gresham.ac.uk/lectures-and-events/medieval-carols